Sir Locksley of Inverness Beyond-the-Wall

Locksley and Palomides came upon the small caravan of wagons shortly after mid-day. They were in the hills above, looking at the valley below, hidden from view by the trees lining the ridge. They’d see a flash of light at times, the reflection dancing along the close confines of a line of dust. They could see a tight-knit collection of wagons with what appeared to be wounded stragglers following. There was an elaborate coach in the lead, as well as a body laid out in the second cart that was being pulled by four men. Palomides sent Amal, the Immortal, ahead to investigate, while Locksley suggested that Brennis go with him. When Palomides bristled at the suggestion, Locksley said the group was obviously armed and would likely attack the man, thinking they were being attacked themselves.

“And why would they think to attack Amal?” the Persian asked, looking down at Locksley from the camel’s great height.

“Why?” Locksley smiled up at him. “The man does nae speak the King’s tongue, an’ the Knight nearest ‘im is ridin’ some fabled beast none ‘ave heard tell of.”

“Granted,” the Knight said with a nod.

“He’s nae apparelled like a man about here.”

“Apparelled?”

“His arms?”

“He is Immortal,” Palomides explained.

“Aye. Immortals are nae from hereabouts now, are they?”

Palomides thought for a moment and nodded, then said something in Persian to Amal, and the Immortal pulled up on his reins and waited for Brennis.

“Go,” Locksley said. “Mayhap they wist o’ the Queen?”

“I can see why Sir Lamorak struggled to understand you,” Brennis grinned, kicking the horse’s flanks; together the two men set off at a gallop along the trail.

“Ye ha’ nae issue with my tongue? My clatterin’ tongue, as Lam likes to say,” Locksley asked, the two of them watching Amal and Brennis follow the trail down the long sloping hill.

“I’m knowing yer uncle for a many of years,” Palomides grinned.

“An’ is a ‘many of years’ a long time, then?” Locksley laughed.

“Many long times,” Palomides smiled.

“An’ is ‘e a goodly man, my uncle?” Locksley asked after a short silence.

“As goodly a man as ever I’ve met.”

“A lettered man,” Locksley pointed out.

“That he is. He knows the words I mean to speak, even afore I say them. He can quote a great many tropes of a great many scholars.”

“An’ say ye that again? Tropes?” Locksley said.

“Any of the ten arguings used in skepticism, to refute dogmatism.”

“An’ think ye then that I’m my uncle’s flesh made whole? I wot not what that is…dogmatism?

Palomides laughed. It was loud, and sudden, and he slapped his thigh as he looked down at Locksley. “Dogmatism! It is a big word, no! It’s meaning is to affirm a judgement, linked to principles which are true a priori, and not truth as seen with evidence.”

“By all the gods old an’ new!” Locksley said with a laugh. “Ye were Grummer’s twin bairn brother as ever I saw!”

“I have heard it noised about some,” Palomides smiled. “It’s the Papish words, aye?”

“Aye,” Locksley smiled. “And about ever’ other word therein,” he added.

“What it means, a priori, is this: Were I to say, ‘Every apple is a fruit,’ it is a priori, because it shows reason. It is reasoning. Do you see? It is not a statement, or a fact about a specific, because we know all apples to be fruit. Yes? Were I to say “Apple are sweet,” it is a posteriori, which is something you know. It does not have to be proven, it is known.”

“Which means what?”

“Those men down there, are in flight.”

“And ye ken this, how?”

“They have wounded. As can well you see. A priori. Those more grievously wounded men are tended to by others. Those not, tend to theirselves. A posteriori. It does not have to be proven. It is seen.”

“Then why send riders out?”

“Details.”

“I dinna ken,” Locksley said with a slow shake of his head. He was thinking Palomides was worse than Grummer when it came to speaking in riddles. The men were meant for each other. At least with Grummer there was laughter, and whoring, and jousting. Palomides was from another world Locksley would never understand.

“What details?” he finally asked.

“They were attacked.”

“So said ye,” Locksley replied.

“But by whom? And wherefore?”

Sir Lamorak de Gales

“King Pellinore, ye say?” Locksley noted, briefly looking at Palomides as Amal nodded. “An’ Brennis ‘as gone off t’ hunt for ’emt?”

“This one says they have had no food. They are in danger, as they must flee,” Pellinore translated.

“An’ Guenevere?”

“She will not tarry. She seeks Launcelot, and no alarm will keep her from her prize.” He said it without hesitation, and Locksley thought maybe it was from some past experience shared with Grummer.

“But Launcelot is ahind of us! Did Brennis nae say this?”

“To whom? Pellinore lays ill. His daughter rules in his stead — or at least, until Lamorak should arrive — and this one says she will not abide by the rule of men.”

“Which means what?”

“Lamorak is her liege lord, and she will heed no other but he.”

“She what? An’ what about the other woman?”

Palomides turned and looked at Amal. Locksley watched the man as he listened, his brows quizzical as he shook his head slowly, speaking again. Amal nodded, pointed to the East, and sat silent. Locksely turned to look up at Palomides once again.

“This one says there was no other woman,” Palomides reported.

“There were two women, both bound for Camelot. Pellinore’s daughter, an’ his sister’s bairn. A kinswoman. Lamorak knows her well. What of her?”

Palomides turned to Amal and spoke at length; he nodded when the man answered. Locksley watched as Palomides slowly stroked his beard, lost in thought. Locksley wished the man would say something, but waited until Amal the Immortal was finished talking. He looked up at Palomides high on his camel, still stroking his chin and looking at his booted leg where it sat crossed in front of him on the saddle.

“An’? What did ‘e say?” Locksley asked at last.

“They were Saxons, but it is more than that; there was a man with them wearing a blue cloak.”

“An’ what of it?”

“He is known.”

“Known? How?”

“He is the paramour of LeFay. Know you the name LeFay?”

“Who is he?”

“He is in reality, the sister of the King. And this man, Accolon of Gaul — an enemy to all and sundry — has taken this other woman you speak of.”

“We have t’ rescue ‘er,” Locksley said.

“And so we shall. Be it that Morgana LeFay is by turns the lover of both Sir Turquine, and this Accolon of Gaul — with neither man knowing the other’s intent,” he said with a smile. “And also, it is nosed about in the villages, that this Turquine has a Keep, and therein this self-same Keep is where Grummer and Ector are held.”

“Ye dinna can know that,” Locksley said with a sneer. “The man speaks what he speaks, not a Saxon tongue.”

“Nay, not a Saxon tongue, but a Gallic one, for we were one and twenty years in good standing with Gaul. And this man in the blue cape is called Accolon the Gaul. And his Saxon soldiers are from Gaul-abouts, across the way.”

“And so ye say, but how?”

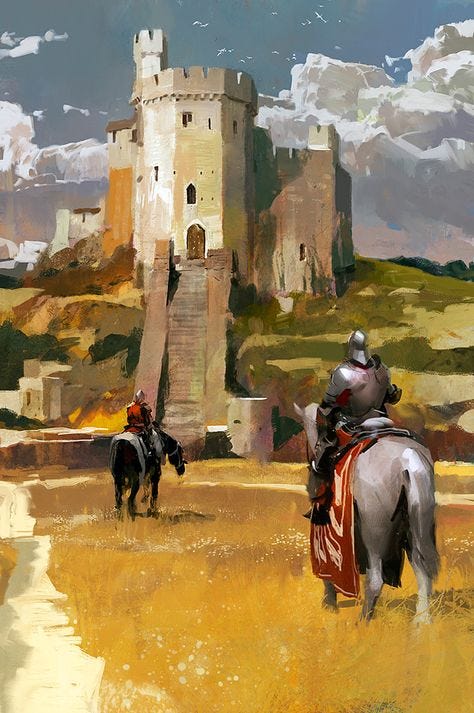

“One of the Gallic horde lay wounded on the field, and ere the Squire could put the man to sword, Amal spoke to him. The man spoke of a great Keep. It is this castle to which the Saxon horde has fled.”

“An’ so we ride, endlong of each, ’til we find this Keep?”

“Aye, but first we needs must wait,” the Saracen said, looking down at Locksley.

“Wait? For what?”

“Would you attack a castle unarmed?”

“We have arms.”

“That we do, but erst shall we send for Lamorak and Launcelot. Then shall we be fully armed with the two greatest Knights of the realm. Mustafa!”

I am getting a little lost in all the names and relationships here, Ben, but I am enjoying the hell out of it. I look forward to the next.