Our story so far…

Having gone off in search of the mysterious smoke and finding the Camp of the Orkney Knights at the end of it, our determined heroes make their way back to the camp where they left Brennis and the horses. It is decided that one of the Boys has to go back to the Queen’s Camp in search of aid, and food, and whatever else…

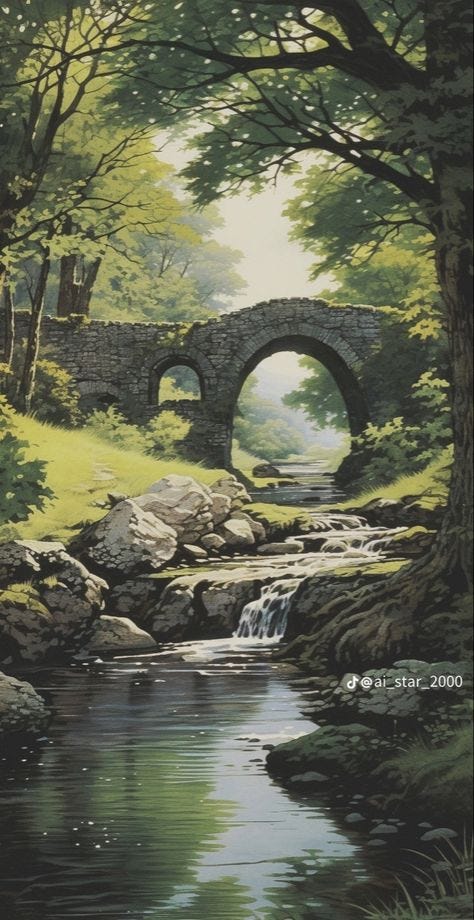

The Bridge at Hollybourne Park

CHAPTER SEVEN

THE BRIDGE AT HOLLYBOURNE

The Bridge at Hollybourne was an old Roman bridge stained with a light patina of mottling moss, surrounded by a copse of trees and a field of daffodils beaten to the ground by a relentless rain that showed no signs of letting up. Huge pools of water surrounded the bridge and outlying areas; the trail they’d been following was nothing more than a muddy track now, gently sloping into the water. The rain fell in sheets, teased by a cold wind and puncturing the pools of water with a merciless savagery that made the three riders huddle under their cloaks.

There was an abandoned stone hut on the far side of the field that was overgrown with moss and grass. It was hard to know if the hut had been built among the trees, or if the trees had grown up around the hut. Saplings were growing on the roof which had partially fallen in on itself. There was no telling how old the hut was; it seemed that it had always been there. Lamorak remembered being on the run, hiding, and sleeping there more than once during The War of the Twelve Kings. As far as he could see, it was the only high ground around, and this was where he’d said he’d meet Palomides anyway. It would’ve been the perfect place for them to pitch the pavilion, except for the pools of water.

He looked around and then pointed to a small clearing back among the trees. Vergil looked and then nodded, guiding the three pack horses he was leading across the field of water. The horses’ hooves made plopping noises whenever they hit the water at just the right angle. The water splashed around them, washing the muddy trail off the horses’ legs and plastering golden petals of vanquished daffodils on their wide breasts like badges of honour. Vergil urged the horses on and they were soon out of the water. He rode up onto the high ground and as far into the trees as he could, then waved a thin arm in the air, and Lamorak nodded.

“We’ll camp here. There’s no need to be out in this kind of weather,” Lamorak said.

“I don’t think I could get any wetter,” the woman complained.

“Precisely,” he said, urging his horse forward.

They set up the small pavilion and Vergil somehow made a roof out of the odds and sods he’d picked up on their travels over the last months. He even managed to make a fire big enough for them to dry themselves off. When the camp was secure, Vergil set off into the woods. He returned an hour later with three rabbits and a variety of wild tubers, roots, greens, mushrooms, leeks and herbs. He skinned the rabbits, cleaned them, then cut them into large chunks, thinking he’d make a stew. The salt was wet, but he used it anyway. The sage, rosemary and thyme he’d found helped with the flavour, but the stew was too thin to be called a stew; it was more like a soup.

He could hear Lamorak inside the pavilion pushing himself into the woman and would’ve gotten up to watch, but decided against it. They’d been at it every night for three nights now — only it wasn’t night now, was it? There was no doubt the woman thought Lamorak meant to wed her, but Vergil knew that was a lie. Lamorak would tire of her soon enough, and when he did, he’d give her to Vergil, and then she’d know for certain, wouldn’t she? Vergil knew he’d have to fight for what she willingly gave to Lamorak — and he would, he knew; he always did. When he was finished with her they’d take her to some nunnery somewhere, knowing the woman would never see freedom again; she was always praying anyway.

Vergil picked up a bowl, dipping it into the stew and tasting it. He nodded to himself and looked at the pavilion again. It was quiet. He supposed they were done, for now. He looked at the pavilion and saw Lamorak’s broadsword leaning against a pole. It would take a while for the stew to render down, so he stepped to the entrance of the pavilion and picked up the weapon, struggling with the weight of it, looking at the edge. He took the small whetstone out of the pouch he carried and set about honing the edge. There were small nicks from the battle Lamorak had fought three days earlier.

When he was satisfied the blade was sharp enough, he called out.

“Lam. The stew’s done.”

Lamorak stepped out of the pavilion, paused, and looked up as three riders came out of the woods, following the trail. He was wearing his gambeson which he pulled closed, tying the laces tight as he casually walked toward the lorica segmentata and the maille hauberk hanging in a tree. The woman came out of the pavilion, tying the bodice of her dress and stopped, looking at the riders.

“Do you know them?” she asked Lamorak.

“I don’t recognize them, no,” he said, ducking his head as Vergil slipped the lorica over his head. Vergil turned, looking over his shoulder as his fingers fumbled with the laces and stays. “I’m the one who should be nervous, not you,” Lamorak said, grinning.

“What do they want? Are they outlaws?” he asked.

“Well, if they are, they’re not very good at it, are they? That boy looks underfed,” he laughed.

“What are you going to do?” the woman asked.

“Vergil,” he said, holding the hauberk out. The Squire took the mailed jacket and slid it over Lamorak’s head, adjusting it to fit over the lorica, pulling the sleeves down as he ran back into the pavilion and came back out a moment later, carrying the chaussons. He held them while Lamorak stepped into them, still watching the three riders. He patted Vergil on the shoulder, nodding in the direction of the three riders. The skinny boy spurred his horse forward at a gentle trot.

“One of them’s coming,” the woman said.

“I see him,” Lamorak said.

“What do you think he wants?” she asked.

“Coming to offer a challenge, I’d expect,” Vergil said, stepping behind Lamorak and helping slip the aventail over his head. He pushed the overhanging chain under the hauberk and then ran back into the pavilion to retrieve the jerkin, which he secured with his belt and scabbard. He went to the fire and picked up the broadsword, running a finger against the edge.

“Not the sort of day I’d choose for jousting,” Vergil said, pausing to watch as the rider approached. “It’s got a new edge,” he said.

Lamorak nodded.

“A fine day for a tilt,” he said with a laugh.

They watched as the boy approached, stopping a distance away and leaning forward in his saddle. “I’ve not come to challenge you,” he said, by way of introduction.

“We’ve no dinner to offer, if that’s what you’re looking for,” Vergil called out, standing in what little shelter the trees had to offer.

“That’s a shame,” the boy laughed, holding up two pheasants. “We’ve yet to break our fast for the day.”

“Who are you?” Lamorak asked, stepping forward and accepting the gift. He tossed them to Vergil who began preparing the birds.

“Brennis,” the boy said.

“Brennis?” Lamorak asked, turning to look up at him. “I hardly recognized you, lad!” he laughed.

“Do I know you?” Brennis asked.

“Of course you do! Not as well as your mother does!” he laughed, turning to look at Vergil. “He’s the boy from The Red Lion. I’m Lamorak deGales!”

“And you think I know him?” Vergil asked. “He doesn’t even know who you are.”

Lamorak considered. “What are you doing out here? And who are your friends?” Lamorak asked, looking across the field. “Invite them in. We’ll cook up your pheasants and enjoy a good meal.”

“I’m a Squire now.”

“A Squire? To who?” he asked, looking at the knight seated on his horse. “I don’t recognize his shield.”

“There’s nothing on it, but that’s Sir Locksley.”

“Locksley? Grummer’s Squire?”

“You know him?”

“I know of him.”

“Well, he’s not here to challenge you,” Brennis said, shifting in the saddle, looking at Vergil as well as the woman standing at the opening of the pavilion. “We’re looking for you, in fact,” he added.

“For me? Well, I’m not sure if I should be happy to hear that, or not,” he laughed. “Why are you looking for me?”

“To warn you,” Brennis said, looking back over his shoulder where Geoffrey and Locksley sat waiting, patient for the moment.

“Is it war, then?”

“War?” Brennis said.

“What else is there to warn me of?”

“We’ve come because the Orkneys have taken to the field, looking to kill you,” Brennis said.

“Me?” he laughed. “When the best of them is Gawain, and I’ve lost count of how many times I’ve unhorsed him?”

“Perhaps I should let Sir Locksley and Geoffrey explain?”

“Geoffrey? What’s he doing riding without Grummer?”

“I’ll let them explain,” Brennis said, turning his horse and riding off.

Vergil stepped out of the cover of the trees and stood beside Lamorak.

“What do you think that was all about? Where’s Grummer?”

“We’ll know soon enough,” Lamorak said.

Lamorak de Gales

They shared a meal of dried bread soaked in grease that Vergil heated up in a pan on the fire; there was also roast pheasant as well as the stew he’d made yesterday. They ate under the cover of an overhang Vergil had tied among the trees, the rain puddling on top and running off the edges. Smoke from the fire winnowed through the trees and branches, and Brennis watched it as he ate, grateful to have finally broken his fast.

He tried not to think about another uncomfortable night of sleeping in the rain. There was three bottles of wine they shared as they ate in silence, and he felt it burning in his chest as he took a large swallow. He found himself staring at the woman, wondering where she’d come from and where she thought she was going.

When she finished eating, he watched her as she stood up and walked out from under the cover, sitting on a log in the rain, looking out over the pools of water that stretched out before her.. The clouds cleared, revealing a pale moon rising above the distant mountains. The setting sun broke through the cloud cover and let in shafts of light that reflected in the water.

Brennis stared, watching the clouds break apart, and saw Lamorak sitting back, looking stunned — as if he’d stared into the flames of the fire for too long. He took a drink of wine, passing the bottle to Vergil, slowly shaking his head as if he’d asked himself a question he was unable to answer. Brennis looked at the woman again, telling himself it had to be a coincidence — the world is chock full of coincidence — and then he looked at Geoffrey who was staring at the woman.

It’s people like Geoffrey who start rumours, he knew. If he finds out she’s a Druid, she’ll be branded a witch.

“And where’s Godfrey?” Lamorak asked, distracted. He was wiping his greasy hands on his jerkin, Brennis noticed, staring out at the woman again. He turned when Geoffrey spoke.

“He’s gone off t’ warn yer Da’,” Geoffrey said, chewing around a mouthful of bread, and staring at the woman.

“My Da’?” Lamorak asked, the spell broken.

“Aye. He’s with the Queen,” Locksley answered.

“Why would the Queen be here?” Lamorak asked. He looked confused.

“Lancelot left Cam’lot with Lionel. The Queen’s set off in search of ‘im,” Geoffrey said, finally looking away from the woman and smiling at Lamorak, shrugging his shoulders lightly. “As she is wont to do,” he added with a smile. “I thought you knew?”

“Me? I haven’t been to Camelot in months. Didn’t want to see Tristan, under the circumstances.”

“What circumstances?” Locksley asked.

“I wanna fuckin’ kill ‘im,” Lamorak said with a slow shake of his head. “Wait. Lionel? Not Ector?” he asked. “It’s not like Lance to go anywhere without his little brother,” he added.

“ Aye, ’twas a great mal-ease with how they were fore-fared, I still say. ’Twas feloniously done as well, Lam! Both men, all but naked of arms. Him an’ Grummer prised away by the Orkney boys, an’ so enslavered to Tarquine,” Locksley said, staring into the fire.

“What? Why? Those two are no threat to anyone.”

“The Orkneys ‘ave long promoted ‘ow it was yer Da’ what slew theirs. They mean t’ avenge their Da’s death, with yours. A blood oath from out of the Olde Ways,” Locksley said.

“It was as much to the dismay of us all,” Geoffrey said, staring purposely at Locksley before picking up the wine bottle and taking another drink.

“But why take Grummer out of the game? It is Grummer they want to take out, I’d think?”

“Aye. We come up on Ector but over-morn. The boy, too. Locksley took ‘im t’ be his Squire,” Geoffrey explained.

“Now, why would you do that?” Lamorak asked Locksley, looking at Brennis. “He’s too young to be your Squire.”

“Ever’one deserves a chance,” Locksley said. “He’s no different.”

“He can’t be any more than fourteen.”

“I’m seventeen, and I’m just as good with a sword as the next man,” Brennis said, hoping there was an edge to his words that made them sound menacing.

“Ye doan even have a sword,” Geoffrey reminded him.

“I suppose he’s taken them to his keep, then?” Lamorak said, ignoring the boy and turning to look at Geoffrey.

“ ’Tis where we’re bound,” Locksley said.

“Planning to challenge him, are you?” Lamorak smiled, remembering the boy who was once upon a time this knight; Brennis looked at Locksley, thinking the young Knight would take offence to the old man’s tone.

“If I have to,” Locksley said with a nod.

“And what exactly does that mean? If I have to?” he said, mimicking Locksley. “This is no child’s game, Lock. He will kill you.”

“Geoffrey seems t’ cog on it might be better if we slip in under the moon an’ free ‘em.”

“Cog on, is it? Up to your old tricks again, are you?” Lamorak said with a smile at Geoffrey.

“I do the best I can,” Geoffrey replied. “I do what’s best for me, as well ye know.”

“It’s what makes you the man you are,” Lamorak smiled. “Or is that The Boys? Because there’s never just the one of you, is there? You’ve your Uncle’s blood, Lock, and your Da’s,” Lamorak said, looking at Locksley.

“He does at that,” Geoffrey said.

Brennis looked at the man, surprised that Geoffrey would reveal what he’d told Locksley was to be kept secret. He looked at the man and Geoffrey smiled.

“Lamorak’s known him since he was a child,” Geoffrey explained.

“You don’t want anyone to know you’re kin?” Lamorak asked.

“Grummer thinks it’d be wiser if no one knows,” Geoffrey said.

“Why? What’s the old bastard up to now?”

“Ye doan know who the lad is?” Geoffrey asked, shocked.

“Should I?”

“He was made Knight of the Field by your Da’, hisself.”

“No! That was you?!” Lamorak said, caught off guard. “I’m beyond grateful,” he smiled.

“Why were you not there? At the battle?” Brennis asked.

“I was a day late,” Lamorak said, taking the wine bottle Vergil held out to him. Brennen thought it was remarkable that the Squire knew when Lamorak needed the wine.

“Aye, a day late an’ a penny short,” Geoffrey laughed.

“I was being chased by a pack of twenty Saxons, if you must know. In fact, I hid in that stone hut, right over there,” he added, pointing to the hut in the distance.

“Only twenty?” Geoffrey smiled.

“They came upon me naked, in my pavilion.”

“I take it by naked ye doan mean unarmed,” Locksley smiled.

Lamorak turned and looked at him. “You’re not going to be able to hide in plain sight if you can’t pretend not to know me.”

Brennis watched the woman stand up, staring out over the water and facing the setting sun. She spread her arms slowly, wide, her shadow a jagged cross behind her. He watched her as she turned, looking at Lamorak, and he wondered what she was up to. It was obvious she was a follower of the Old Gods, Brennis thought. It was possible she’d once been a friend of the Myrddin, and that maybe he’d taught her a spell or two, or maybe an incantation? It was also obvious Lamorak didn’t know any of that — probably didn’t even care to be honest — as long as she was willing to fuck him every night, which he was sure she’d been happy to do.

“Nim?” Lamorak called out to her. “What’re you doing?”

“You have your own path to follow, Lamorak de Gales,” she said, staring into the twilight. “It cannot end well for you.”

She turned to look at him.

“What are you doing? Come inside. My bed’s getting cold,” he smiled.

“Your path and mine end here. Tonight.”

“Tonight? What, now?” he said.

“Prepare yourself, Lamorak deGales.”

“Prepare myself? Prepare myself for what?” he asked, and stood up. He walked to the edge of the large pool. He could see the setting sun in the broken surface

She started to walk into the huge pool of water in front of her.

“What are you doing?” Lamorak asked, standing up. “Nim! Where are you going?”

“I’m already gone, Lamorak. You won’t see me once I pass through the light of the fire. My resurrection is at hand!” she called out, stepping into the encroaching darkness.

“Nim?” Lamorak walked to the edge of the camp, looking out into the shadows.

Brennis heard a splash, and then there was silence. He looked at Lamorak’s feet, at the waves gently washing up against the man’s feet; Lamorak called out her name once more.

Lamorak and Locksley slept within the close confines of the pavilion; Vergil and Brennis — as the Squires — lay close to the fire’s warmth, while Geoffrey sat with his back against a tree wrapped in a bear rug. He slept with his longbow on his lap, an arrow notched, and three more arrows stabbed into the fresh ground around him. He slept fitfully, even though the horses had been hobbled and secured for the night and there’d been no sign of wolves.

Locksley woke up early, and stepping over Brennis and Vergil, slipped outside to escape the closeness of the pavilion. Maybe the woman leaving when she did was a good thing? He’d heard stories of Knights capturing fair young maidens, and a part of him wondered if that was what had happened. While his mother may have made up stories and tales of endless adventures, he knew the reality was different. If that woman somehow wandered into the Orkney camp she’d be raped and tossed to the side, probably left in a ditch with her throat slit.

Locksley paused to watch the sun brushing through the trees, the morning mist a visceral cloud playing with shadows and light in the trees. Sunlight mirrored against the water, the wind strumming across the face of the smaller ponds like a minstrel’s hand on a lute.

Locksley kicked Brennis gently to the side, and the youth rolled over, pulling the deer robe over himself. Locksley busied himself with the fire. He brought the embers back to life, blowing on them and coaxing them with a tease, touching the dried leaves and grasses he’d gathered until they stirred to life and burst into flame. He built the fire up like a funeral pyre to a king.

He heard a sound unlike anything he’d ever heard before and looked to the edge of the forest. There, magnified by both the light and the distance, two of the largest beasts he’d ever seen, surrounded by eight riders.

👍🏻 👍🏻 👍🏻! Great.