A word to start…

And one more thing!

In our last post, we met the beautiful Lady Gwenellyn as well as King Pellinore and his daughter Miriam. They are in the Queen’s camp, as she searches for Lancelot. Locksley arrives in the camp seeking aid from the Queen, only to discover that King Pellinore has been “stroked by the Hand of God,” while having breakfast with the Queen. It is here that Locksley is given the name of The Beggar’s Knave…

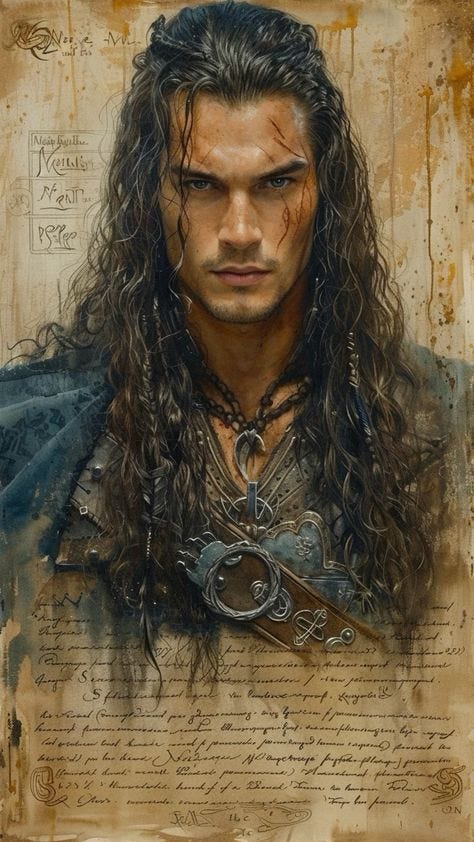

Locksley, The Beggar’s Knave

CHAPTER FIVE

OF PLOTS DEVISED AND

DEEDS DONE IN THE DARK

Locksley was certain he could smell smoke from somewhere in the distance, and drew himself up in his saddle as he followed the scent. He looked at Brennis to his left as he stood in his stirrups, searching the air. Whatever it was he thought he smelled, Brennis noticed it at the same time, and turning in his saddle, looked at Locksley with a quizzical turn of his head. They smiled at each, and Locksley nodded. They both slowed their horses to a walk, as Brennis began inspecting the forest floor ahead of them, searching for any signs of a possible ambush. Locksley also looked down at the forest floor, and following Brennis’s gaze saw how the leaves ahead of them seemed to have been kicked over, their slick undersides exposed and catching the last rays of sunlight.

Locksley looked at the sun. It was low in the sky and threatening to drop down behind the distant mountains. He could see clouds in the distance — the clouds shot through with rays of sunlight — and told himself it was going to be a miserable night.

The impermanence of Nature, he thought, wondering where the thought even came from in the first place.

No doubt, that would be Uncle Grummer’s influence, he told himself.

Locksley turned his attention back to the trail. He was certain it was smoke, now. It was faint, still lost somewhere in the distance, but together with the musky scent of wet leaves kicked up from their horses’ hooves — and whoever they were following, he reminded himself — he told himself he had to do something. He stopped.

He was watching The Boys, seeing how they both stiffened at once the moment they caught the scent as well. Locksley nodded and gave his reins to Brennis before climbing down from his horse. He drew his sword, taking off his belted scabbard as he pulled his shield off his back with practiced ease.

“What is it yer thinkin’ yer doin’?” Godfrey asked in a hoarse whisper, looking about with obvious dread. He was looking at the surrounding woods, probably thinking it was a good place for an ambush, Locksley thought — and it was he could see, with high aspen trees caught in a gentle breeze, and birch, on both sides of the trail they were following. The night was coming fast, though; twilight would soon be on them which was even more reason to be searching the trail ahead as far as Locksley was concerned. He watched Godfrey draw his longbow out and string it as he sat crosslegged in the saddle. He took an arrow out of the quiver hanging from his saddle, then lifted his leg over and jumped down from the saddle. Geoffrey was quick to step down as well.

“Surely, ye smell it?” Locksley said, looking at the Boys.

“Aye, that we do,” Godfrey smiled. “An’ it’d do ye well t’ keep yer voices low. If ye can smell their smoke, it’s for certain they’ll hear yer braying like ye were a bitch in heat.”

“Sir Knight,” Geoffrey added with a smile.

“Sir Knight,” Godfrey acknowledged,

Locksley looked up at Brennis. “We doan know what’s there, so I’m gonna have a look. The first thing ye’ll wanna know about bein’ a Knight, is that if yer gonna to fight on foot, it’s best t’ take yer scabbard off. Ye doan need to be trippin’ yerself up,” he added, passing the scabbard up to the boy.

“I’m thinking this is nae place for us to be making our camp,” Godfrey warned.

“Aye, but also, too, ’tis not my intent t’ stumble blindly into a camp I know nothin’ of,” Locksley said. “This is one of the many tactics of War I’ve been taught — always know yer enemy’s strength.”

“Taught t’ ye by whom? We’re not at war,” Godfrey pointed out, “an’ havena been for some years.”

“I’m going t’ scout ahead, t’ be sure, until I can determine where the camp is. Ye can stay here if yer afeared,” he said.

“That tactic doan sound like a sound tactic,” Geoffrey said, and handed his reins up to Brennis. “Which means we’ll have to go with ye jest to be certain ye doan go an’ get yerself killed.”

“Well, of course,” Locksley said. “I canna have ye not sayin’ something untoward, as well; I’d expect no less from ye.”

“Is he being facetious?” Godfrey asked Geoffrey, walking his horse and giving his reins to Brennis as well.

“Nae, that’s irony,” Geoffrey said. “He doesna know the difference.”

“It won’t be irony unless he actually finds them,” Godfrey reminded him.

“I think ye have me confused with m’ uncle — ”

“We’re not t’ let ye call ‘im that,” Geoffrey warned, looking up at Brennis.

“Why not?”

“Sir Grummer’s orders. We din’t agree to it, but what could we do? He’s willin’ t’ be yer uncle, but he doan want nae man t’ know yer ‘is kin. Is that understood, boy?” he added, looking up at Brennis.

Brennis stared down at the large man, noted the endless melody of scars that crisscrossed his face and nodded slowly.

“An’ why would m’ uncle say that?” Locksley asked.

“Ye dinna ken what ye did that day, do ye lad?” Geoffrey asked. “Ye didna hear the Queen an’ how she recalled yerself bein’ presented as The Knight of the Field, newly made by Pellinore? That’s not a title they give off lightly.”

“I saw none of that,” Locksley said, leaning on his sword.

“According to all what’s said, t’was King Pellinore what killed King Lot — as it should be. Lamorack de Gales is the son of King Pellinore. One of the best knights out there. Without a doubt, in the top three,” Geoffrey said.

“Aye, but it’s changeable, ain’t it? The top three, I mean?” Godfrey said.

“Aye, that it is, without a doubt,” Geoffrey agreed.

“Yer natterin’ again, Boys,” Locksley reminded them.

“Aye,” Geoffrey said. “That’s on account of Lamorack bein’ a man who’s loved by all.”

“Ye doan sound very convinced about it,” Locksley pointed out.

“Well, I’ve heard things — we’ve heard things. So he’s not always in the top three with what we heard, is he?” Geoffrey asked.

“He’s certainly nae the Knight his brother is,” Godfrey said.

“Polar opposites.”

“Which brother?” Locksley asked.

“Percy,” Brennis said.

“Percival de Gales,” Geoffrey corrected him. “Again, easily in the top three,” he said, and Godfrey nodded, agreeing; they both looked up at Brennis, and he nodded as well.

“You still haven’t told me anything to dissuade me,” Locksley said.

“The Orkney knights have put a bounty on Pellinore’s head. But Pellinore’s old now. He was old when I was young. But now…now, it’s been put about that Lam’s been fuck-struck by Lot’s Widow. And because he’s the son of the man what killed their father, they wanna kill him as well.”

“Lamorack?”

They both nodded, satisfied.

“Interesting story, but I don’t see why ye think it has anythin’ t’ do with me not callin’ Grummer me Uncle?”

“Ye were there when Lot died, aye?” Godfrey said.

“As ye well know I was.”

“Say ye now the troth of what happened.”

“Lot got in behin’ us qa an’ swung ‘is war hammer. I got m’ shield up an’ saved Pellinore from havin’ his brain-pan bashed in.”

“Aye, we know that. But we want to know is, what really happened?”

“I told ye,” Locksley said, growing impatient.

“An’ I’ll tell ye why we doan believe ye,” Geoffrey said, leaning on his bow and looking at Locksley. “A man has his back turned t’ someone else, an’ that’s usually ‘ow it happens — his bein’ killed, I mean. Some Berserker walks into battle swingin’ a mace on a three foot chain, holdin’ an axe in his other hand — ”

“Or a hammer,” Godfrey interrupted.

“Aye, or a hammer. So Lot swings ‘is hammer down an’ ye put yer shield up to stop it, but the hammer destroys yer oaken shield. Pellinore starts to turn, but Lot’s ready to swing his hammer again.”

“About t’ kill the ol’ King,” Godfrey said.

“That’s why ye did it yerself, dincha? That’s why it’s best nae man knows the truth of what ‘appended that day ye were made the Knight Of The Field. It won’t take ‘em long t’ figure out who ye are, or what ye done.”

“It won’t take ‘em long t’ realize Pellinore din’t kill their da’, ye mean. An’ when they do, they’ll be comin’ after yerself, an’ Sir Grummer.”

“An’ that’s who ye think is out there,” Locksley said.

“It’s always best to err on the side of caution,” Brennis said.

Gareth, the Youngest of the Orkney Knights

Locksley could hear someone coughing in the distance, followed by the muffled sound of voices and the cadence of shrill laughter. He ducked his head down, thinking maybe he’d been seen, or that maybe they’d heard him. He looked at The Boys, one of them was to the left of him, and the other to the right, but neither of them paused, or hesitated. He began crawling forward again at a snail’s pace. They were each of them approaching the camp, hoping to hear something useful. Locksley wondered what information Geoffrey thought would be useful, as much as he wondered how he and Godfrey were now following Geoffrey’s lead.

They crawled to the edge of a long ridge where a large thicket of trees grew — aspens and willows that caught the wind, bending with a rustle of leaves — and he knew he’d be able to stand up and remain out of view. Locksley looked to The Boys, but both of them were already standing with their bows ready — each with an arrow notched — and he had to ask himself what use he’d be with his sword if it came down to a fight? The Boys could easily kill every man in the camp with their arrows if they wanted.

He moved as close to the ridge’s edge as he could, making certain nothing he was wearing would catch the fire’s light and give him away as he scanned the camp. There were a total of five large pavilions with a full compliment of Squires and Footmen for each of them. They sat in front of the pavilions, some of the Squires polishing harnesses, the Footmen honing weapons to a keen edge. They shared a common fire, as well as their food and drink.

There was easily twenty of them, Locksley counted. Twenty-five with the Knights.

That’s useful information.

The Knights were in a smaller camp they built within an enclosure of dead trees that once served as someone else’s camp long ago. It was under the low rising ridge because it held back the wind. Two of the Knights were sitting, their backs against the dead trees, drinking from a bottle they were passing back and forth between them, talking, and laughing. Someone was cooking, and the smell of roasting meat hung in the air. Locksley supposed there was no need for a sentry because there was safety in numbers. Besides, the sun had yet to set and who was going to attack a camp of five Knights and their servitors? Anyone hearing them would take a wide berth, or approach and ask permission to pass, or perhaps ask to share a meal. It wasn’t something he’d be doing under the circumstances — those circumstances being that of Grummer and Ector’s capture and the possibility that the very men encamped below were responsible.

Again, that’d be where the useful information comes in handy, he told himself.

“I say the time fer action is now!” one of the Knights said, tossing the bottle of wine to one of the two seated men in front of him. He had a deep voice, and belched loudly, laughing. He was a large man, fully a head taller than the others, with a large moustache that covered both his top and bottom lips. His hair hung to his shoulders in fine curls and coils of vibrant red, matched by the colour of a scar that split his face in half, crossing from his left eye to his right cheek.

Agravaine, Locksley told himself. The scar was a gift from Lancelot — that much he knew. It was a recent memory from the War of the Twelve Kings.

“Doan be a fool, Aggie,” one of the Knights in front of him said, confirming Locksley’s guess. “If we attack we’ll be up on a scaffold faster ’n ye can spit. We have t’ wait ‘til he’s on ‘is lonesome.”

“ ‘E’s never gonna be on ‘is lonesome, now then, is he?” Aggie said, waiting as the third Knight tossed the bottle back to him. He caught the bottle, but wine spilled down the front of his gambeson.

The fourth Knight was near the fire-pit, tending to a large boar roasting on the spit. He turned it every few minutes when it started sizzling and smoking, pouring wine on the carcass and taking a drink at the same time. He offered the bottle to the fifth Knight who declined with a shake of his head. The Knight shrugged, took another drink of wine, and poured more on the roasting pig.

It was difficult for Locksley to get a clear view of the man because he was standing in the shadows. But it was obvious to him they were the Orkney Knights; it was frustrating that he didn’t know which was who. The flags they all flew outside their pavilions were similar — they had the same Coat of Arms stencilled on different coloured backgrounds — and the chain they wore was also similar. It was all fine knowing they were the Orkney Knights, but they’d yet to say anything about the capture of Grummer and Ector.

“I s’pose we can wait another day,” Aggie said.

“Of course we can!” the man beside him laughed. “Tomorrow’s a better day for it!”

“An’ why would tomorrow be a better day for it?” Aggie asked.

“Well, he’s sure to be leaving, won’t he?” the man laughed. “He an’ his two girls. More sport for us then, don’tcha think? We can’t be leavin’ any of ‘em alive t’ tell the tale now then, can we? So, we may as well have a little sport with ‘em.”

“A little rape an’ relaxation!” Aggie cried out with a laugh. “Ye might not say much, Harry, but when ye do.”

“Exactly!” Harry said, and Locksley could see the man reaching for the bottle.

And which one are you, Harry? Gaheris! Of course!

“We’ll not be havin’ any of that!” another voice called out, and Locksley strained himself to see who it was. He squirmed ahead and leaned out over the ridge as far as he could, pulling himself back when he heard some of the loose clumps of dirt bounce down the edge; he hoped maybe one of The Boys had a better view.

“An’ ye doan have to, do ye!” Aggie called out. His deep voice was harsh, sounding angry, almost as if the man was frustrated. “The sooner we get ye t’ Camelot, the better fer all of us, I say!”

“All the better for me t’ be rid of the likes of yerself, Aggie,” the man called in return.

“I’m sure ye’ll be tellin’ dear mommy all about it as soon as yer able,” Aggie laughed.

“The slut!” the Knight seated beside Harry called out — and Locksley wondered who that was.

“Now Moe, doan ye be callin’ out anythin’ like that, yer bein' ‘er bastard son, an’ all,” Aggie laughed. “If she weren’t a slut, ye’d not be ‘ere in the first place, would ye?”

“Leave off, will ye, Aggie?” Moe called out.

“Leave off, yerself, ye slatternly slut’s slip-up,” Aggie called out with a laugh, and Harry echoed him.

“An’ what was that we ‘eard about ‘is fallin’ in the Queen’s tent this morn?” Harry asked.

“I dinna heard tell of that,” Aggie replied.

“I ‘eard ‘em say so when Grummer’s Squire rode in t’ say he was took away by Tarquin,” Moe said, taking the bottle from Harry.

“That was nae Grummer’s Squire,” Harry laughed. “The one wearin’ the tattered maille was more like t’ be a Squire. What was that Pelly’s bitch called him? The Beggar’s Knave?”

“The boy?” Aggie laughed. “He’s a child!”

“Ye wit well who the lad was, then?” the last Knight called out, turning the spit and pouring more wine on the boar.

“Grummer’s lad? Aye. He’s the one what was up with the whores when we got there,” Aggie laughed. “He’s the son of Ambrose, which makes ‘im Prince of Ivanore,” he added. “Father killed him, an’ a good thing, too. The last thing we want is a strong Ivanore on our southern border.”

“Ivanore’s Prince?” Harry asked. “Is it vengeance ye think he’ll be lookin’ for then?”

“Aye. ‘E was just a wee ‘un then, but he’s Ambrose’s whelp all the same,” Aggie said.

“I wit ye know that for certain?” the Knight at the fire called out.

“Aye, that I do, Brother,” Aggie laughed.

“Ye weren’t with Da, or by ‘is side, when it all come about,” Harry reminded the man.

“But well I know it was Grummer what took the boy out of harm’s way. Him an’ the Myrddin’s scourge,” Aggie said.

“That’d be Galen,” the man said, and Locksley watched, waiting as the man stepped into the clearing. “Aye, a bastard all the same,” the man said.

“Who? Galen, or Grummer?” Moe said, a slow smile cresting his face.

“An’ is that how ‘e spoke up against ye when it come to yer intended nuptials with the Queen, Brother?”

“She was nae Queen then, was she?” the man said. “T’was long afore the War o’ the Twelve Kings. T’was back in the Saxon Wars.”

“An’ ye were still in Arthur’s camp,” Harry called out.

“Aye. An’ so?”

“Ye coulda well spoke out when Arthur took t’ yer mother’s bed an’ gat the whelp on ‘er,” Aggie laughed.

“Leave off with that!” Moe called out.

“An’ how was I t’ know the slut was about t’ spread ‘er thighs for what proved t’ be her own kin? I dinna can say whether ‘e knew of it at the time,” the man said.

“An’ ye think it woulda stopped him? Knowin’ it all the same?” Harry laughed. “Would ye nae do it with Morgana, given half a chance?” he called out.

“Leave off, there, with that kinda talk,” the fourth Knight called out.

“Leave off, yerself!” Aggie shouted back, and Locksley could see the Squires and Footmen all looking up at the same time.

“God, it’ll be grand droppin’ ‘im off at Camelot,” Harry said again, looking at Aggie.

“Aye, that it will,” Aggie agreed. “An’ will ye be callin’ on yer Uncle for a boon?” he laughed, as he called out to the last Knight.

“I’ll be callin’ on dear Uncle for what he owes me,” the man said. It sounded as if the man was moving, and soon Locksley saw him. He was tall, and lean, dressed in nothing more than a tunic and lace-up boots. His hair was dark, and hung in front of his face. He ran a hand through it.

“Owes ye? Yer dear Uncle owes ye none,” Harry laughed.

“It’s me what he owes,” Moe said, standing and walking to the fire. He was also tall and thin, but with a pronounced limp and a stooped back. His hair was dark, but for a shock of white on the left side. His beard grew in sparsely — something you might expect with a lad closer to Brennis’s age.

“He owes yerself even less than ‘e does me,” the last Knight said. “The most ye could hope for, is that he knows ye for his son.”

“Leave off, with that now!” Moe replied, picking a strip of meat off the boar.

“Leave off, yerself!”

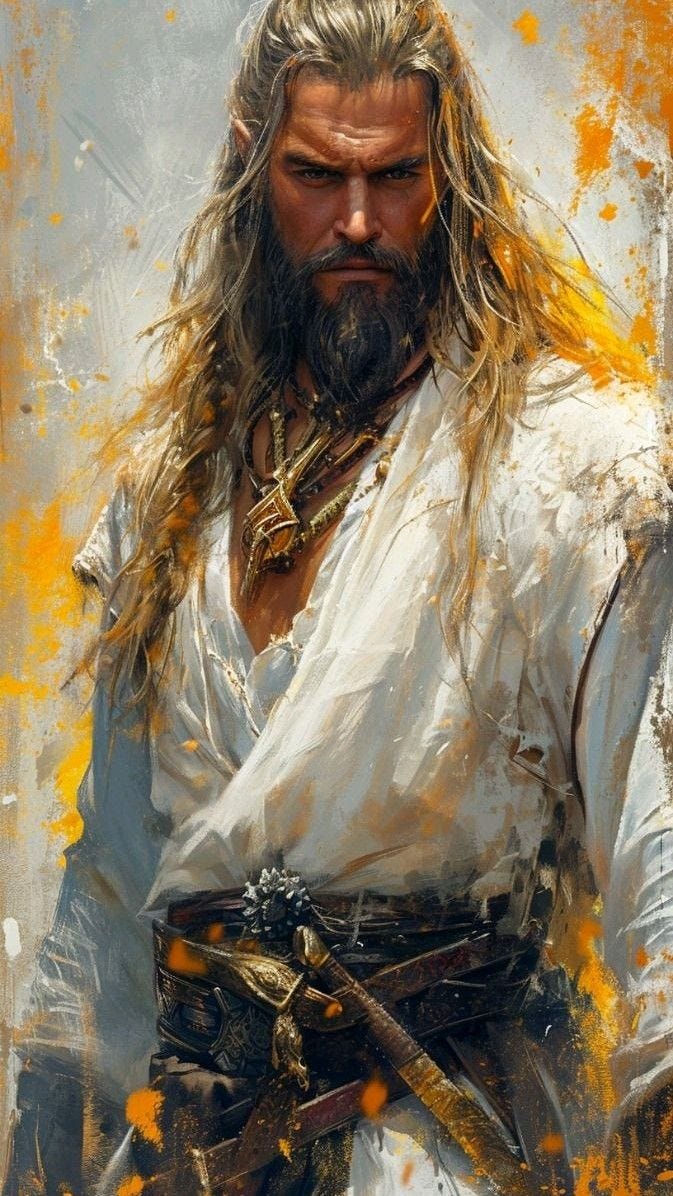

Locksley had no doubt they were the Orkney Knights. It was the five of them together, and he wondered which of them was Gawain. He thought it had to be the older Knight — the one tending to the boar. His once red hair was streaked with grey, and thinning. He was a tall man, broad across the chest, and well muscled, with a drooping moustache flowing into a large beard fanning across his chest. It seemed obvious the tall Knight was the youngest of Lot’s sons — the one they were escorting to Camelot — which meant he was Gareth; Moe, the Bastard, had to be Modred. He’d heard Grummer speak the name enough times. He’d already sorted out who Agravaine and Gaheris were.

“So it’s settled then? We wait fer Pellinore t’ leave an’ then kill ‘im the first chance we get?” Aggie said.

“What about Lamorak?” Moe asked.

“What about ‘im?” Harry asked.

“I hear ‘e’s with that Saracen, nosin’ about,” Aggie said.

“Let him. There’s five of us an’ only two of them,” Harry scoffed.

“His Squire rides one of those beasts. ‘Ave ye not seen ‘im?”

“So? When ye ride ‘im down, ye lance the beast, instead of goin’ for the man,” Aggie said.

Moe laughed. “Ye make it sound as if I’ll be the one chasin’ down the Squire? Is that yer plan then? An’ which of ye’s’ll be facin’ Lam? Ye’ve never once taken ‘im down in all the times ye’ve met with ‘im — not one of ye. What makes ye think ye will now?”

“Running up against a man in the King’s lists at Camelot is hardly the same as facin’ a man in the open field, is it?” Gawain said calmly.

“How can ye say that an’ still call yerself loyal t’ the King?” Gareth said, sounding angry. “Did ye nae hear ‘em? They’re plottin’ t’ take down a King!”

“Aye, the very man what killed yer da’,” Gawain said.

“We’ll wait for Lam at the bridge in Hollybourne Park, is what we’ll do. The road narrows there an’ ‘e won’t ‘ave time t’ prepare. We can get all of them there at the same time. We’re a score an’ five to their ten, at best. All we need do from that, is wait for Pellinore an’ his girls after. Then it’s sportin’ time!” Aggie laughed.

Locksley looked at The Boys, saw them stirring and moving back from the ridge; he slowly dropped to his knees, fading into the darkening shadows; mute.

Sir Gawain, the oldest of the Orkney Knights