Our story so far: Sir Locksley, Knight Beyond the Wall—The Beggar’s Knave—together with Geoffrey and Godfrey, The Boys, Sir Grummer’s Men-at Arms, spy upon the Orkney knights and overhear their plans to set upon Lamorak deGales.

CHAPTER SEVEN

THE BRIDGE AT HOLLYBOURNE

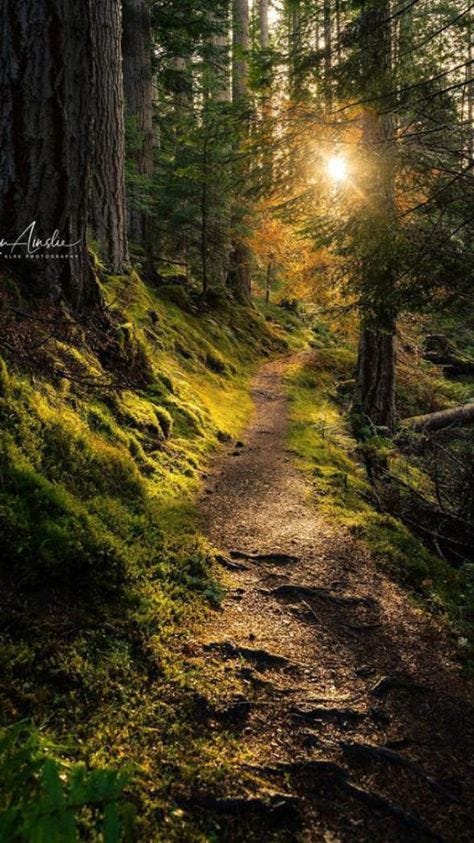

The Bridge at Hollybourne was an old Roman bridge stained with a light patina of mottling moss, surrounded by a copse of trees and a field of daffodils beaten to the ground by a relentless rain that showed no signs of letting up. Huge pools of water surrounded the bridge and outlying areas; the trail they’d been following was nothing more than a muddy track now, gently sloping into the water. The rain fell in sheets, teased by a cold wind and puncturing the pools of water with a merciless savagery that made the three riders huddle under their cloaks.

There was an abandoned stone hut on the far side of the field that was overgrown with moss and grass. It was hard to know if the hut had been built among the trees, or if the trees had grown up around the hut. Saplings were growing on the roof which had partially fallen in on itself. There was no telling how old the hut was; it seemed that it had always been there. Lamorak remembered being on the run, hiding, and sleeping there more than once during The War of the Twelve Kings. As far as he could see, it was the only high ground around, and this was where he’d said he’d meet Palomides anyway. It would’ve been the perfect place for them to pitch the pavilion, except for the pools of water.

He looked around and then pointed to a small clearing back among the trees. Vergil looked and then nodded, guiding the three pack horses he was leading across the field of water. The horses’ hooves made plopping noises whenever they hit the water at just the right angle. The water splashed around them, washing the muddy trail off the horses’ legs and plastering golden petals of vanquished daffodils on their wide breasts like badges of honour. Vergil urged the horses on and they were soon out of the water. He rode up onto the high ground and as far into the trees as he could, then waved a thin arm in the air, and Lamorak nodded.

“We’ll camp here. There’s no need to be out in this kind of weather,” he said.

“I don’t think I could get any wetter,” the woman complained.

“Precisely,” he said, urging his horse forward.

They set up the small pavilion and Vergil somehow made a roof out of the odds and sods he’d picked up on their travels over the last months. He even managed to make a fire big enough for them to dry themselves off. When the camp was secure, Vergil set off into the woods. He returned an hour later with three rabbits and a variety of wild tubers, roots, greens, mushrooms, leeks and herbs. He skinned the rabbits, cleaned them, then cut them into large chunks, thinking he’d make a stew. The salt was wet, but he used it anyway. The sage, rosemary and thyme he’d found helped with the flavour, but the stew was too thin to be called a stew; it was more like a soup.

He could hear Lamorak inside the pavilion pushing himself into the woman and would’ve gotten up to watch, but decided against it. They’d been at it every night for three nights now—only it wasn’t night now, was it? There was no doubt the woman thought Lamorak meant to wed her, but Vergil knew that was a lie. Lamorak would tire of her soon enough, and when he did, he’d give her to Vergil, and then she’d know for certain, wouldn’t she? Vergil knew he’d have to fight for what she willingly gave to Lamorak—and he would, he knew; he always did. When he was finished with her they’d take her to some nunnery somewhere, knowing the woman would never see freedom again; she was always praying anyway.

Vergil picked up a bowl, dipping it into the stew and tasting it. He nodded to himself and looked at the pavilion again. It was quiet. He supposed they were done, for now. He looked at the pavilion and saw Lamorak’s broadsword leaning against a pole. It would take a while for the stew to render down, so he stepped to the entrance of the pavilion and picked up the weapon, struggling with the weight of it, looking at the edge. He took the small whetstone out of the pouch he carried and set about honing the edge. There were small nicks from the battle Lamorak had fought three days earlier.

When he was satisfied the blade was sharp enough, he called out.

“Lam. The stew’s done.”

Lamorak stepped out of the pavilion, paused, and looked up as three riders came out of the woods, following the trail. He was wearing his gambeson which he pulled closed, tying the laces tight as he casually walked toward the lorica segmentata and the maille hauberk hanging in a tree. The woman came out of the pavilion, tying the bodice of her dress and stopped, looking at the riders.

“Do you know them?” she asked Lamorak.

“I don’t recognize them, no,” he said, ducking his head as Vergil slipped the lorica over his head. Vergil turned, looking over his shoulder as his fingers fumbled with the laces and stays. “I’m the one who should be nervous, not you,” Lamorak said, grinning.

“What do they want? Are they outlaws?” he asked.

“Well, if they are, they’re not very good at it, are they? That boy looks underfed,” he laughed.

“What are you going to do?” the woman asked.

“Vergil,” he said, holding the hauberk out. The Squire took the mailed jacket and slid it over Lamorak’s head, adjusting it to fit over the lorica, pulling the sleeves down as he ran back into the pavilion and came back out a moment later, carrying the chaussons. He held them while Lamorak stepped into them, still watching the three riders. He patted Vergil on the shoulder, nodding in the direction of the three riders. The skinny boy spurred his horse forward at a gentle trot.

“One of them’s coming,” the woman said.

“I see him,” Lamorak said.

“What do you think he wants?” she asked.

“Coming to offer a challenge, I’d expect,” Vergil said, stepping behind Lamorak and helping slip the aventail over his head. He pushed the overhanging chain under the hauberk and then ran back into the pavilion to retrieve the jerkin, which he secured with his belt and scabbard. He went to the fire and picked up the broadsword, running a finger against the edge.

“Not the sort of day I’d choose for jousting,” Vergil said, pausing to watch as the rider approached. “It’s got a new edge,” he said, giving Lamorak the sword.

Lamorak nodded.

“A fine day for a tilt,” he said with a laugh.

They watched as the boy approached, stopping a distance away and leaning forward in his saddle. “I’ve not come to challenge you,” he said, by way of introduction.

Lamock deGales

“We’ve no dinner to offer, if that’s what you’re looking for,” Vergil called out, standing in what little shelter the trees had to offer.

“That’s a shame,” the boy laughed, holding up two pheasants. “We’ve yet to break our fast for the day.”

“Who are you?” Lamorak asked, stepping forward and accepting the gift. He tossed them to Vergil who began preparing the birds.

“Brennis,” the boy said.

“Brennis?” Lamorak asked, turning to look up at him. “I hardly recognized you, lad!” he laughed.

“Do I know you?” Brennis asked.

“Of course you do! Not as well as your mother does!” he laughed, turning to look at Vergil. “He’s from the Red Lion. It’s me, Lamorak! Lamorak deGales!”

“And you think I know him?” Vergil asked.

“What are you doing out here? And who are your friends?” Lamorak asked, looking across the field. “Invite them in. We’ll cook up your pheasants and all enjoy a good repast.”

“I’m a Squire now.”

“A Squire? To who?” he asked, looking at the knight seated on his horse. “I don’t recognize his shield.”

“There’s nothing on it, but that’s Sir Locksley.”

“Locksley? Grummer’s Squire?”

“You know him?”

“I know of him.”

“Well, he’s not here to challenge you,” Brennis said, shifting in the saddle, looking at Vergil as well as the woman standing at the opening of the pavilion. “We’re looking for you, in fact,” he added.

“For me? Well, I’m not sure if I should be happy to hear that, or not,” he laughed. “Why are you looking for me?”

“To warn you,” Brennis said, looking back over his shoulder where Geoffrey and Locksley sat waiting, patient for the moment.

“Is it war, then?”

“War?” Brennis said.

“What else is there to warn me of?”

“We’ve come because the Orkneys have taken to the field, looking to kill you,” Brennis said.

“Me?” he laughed. “When the best of them is Gawain, and I’ve lost count of how many times I’ve unhorsed him?”

“Perhaps I should let Sir Locksley and Geoffrey explain?”

“Geoffrey? What’s he doing riding without Grummer?”

“I’ll let them explain,” Brennis said, turning his horse and riding off.

Vergil stepped out of the cover of the trees and stood beside Lamorak.

“What do you think that was all about? Where’s Grummer?”

“We’ll know soon enough,” Lamorak said.

Ben, this is the one I mentioned in my message!