Well, here we are for another warrior’s weekend! Two more chapters to go! Make sure you subscribe before I put the paywall back up, or you’ll lose out on the best deal on SUBSTACK!

In our story last week…We find the party of King Pellinore packing up and leaving. Gwenellyn is returning from a swim in the hot springs high up in the hills. She pauses long enough to look over the camp, and then returns, taking over for Miriam so she might have a chance to use the springs.

This is when we find out that Pellinore seduced the young Princess after her father died, and that Gwenellyn is now able to confront him.

In the meantime, high up in the hills, Miriam hears riders approaching and hides, spying on them as they attack the camp and abduct the Lady Gwenellyn…

And now…

CHAPTER TWELVE

THE QUEEN MORGANA LeFAY

Morgana Le Fay looked out over the courtyard — a dirty, squalid, patch of mud reminding her more of a pig sty than a courtyard — remembering how Turquine’s captive Knights had been forced to work on the construction of his new Curtain Wall. There’d been a torrent of rain that week, cold and hard, and she’d watched as their steaming bodies placed the rocks down in what could only be called the haphazard semblance of a wall. They were beaten men for the most part, she could see that — anyone could see that — but there’d been a surge of resistance that rose up among the Knights at the most unexpected time, Turquine told her.

And that time had come with the building of the wall. Large rocks had been found and brought back for the task — the search had gone far afield, he told her, and at great expense — as the captive Knights were meant to build the wall within a given period of time.

“An’ goddamn if there wasn’t one man who rose up t’ the challenge ever’thin’…an’ it always bein’ the same man.”

“Who?” she asked.

“Who? That goddamned Pict!” Turquine swore.

“What Pict? D’ye mean Grummer?”

“Aye, Grummer!” he yelled. “The man refuses t’ give up an’ bend ‘is will t’ mine. I’ve had ‘im beaten so that ‘e couldn’t stan’, an’ still, in the mornin’, ‘e’s there t’ toe the line. I hate the man an’ ever’thin’ ‘e stands for!”

“Why would ye hate a man that shows such resolve?”

“Are ye daft, woman! A man that brings resolve, brings ‘ope t’ the others! A man like that ‘as t’ be broken, an’ made t’ fear me as much as any other man fears God Hi’self!”

“And ye’d do this with Grummer? A confessed Pict?”

“Confessed? To whom?

“Arthur, you dolt.”

He crossed the room and struck her — hard — without hesitating, catching her off-guard as well as off-balance. She stumbled, falling against the wall and to the floor. She looked up at him from her hands and knees, through the dark curtain of hair covering her face, the grey of her eyes darkening to a leaden colour.

“I’ll break ‘im, or I’ll see ‘im dead!” Turquine shouted, standing over her, his fists pounding against the wall until they bled.

“Then ye’d best do it now, or kill him, because ye’ll ne’er break him. We’re two of the same breed, him an’ I,” she added, throwing her hair back and feeling the soft swell of her lip. She could blood, but that didn’t matter. Not now, she told herself, standing. “Let’s hope ye don’t live to regret that,” she added, standing up straight and looking down at him in defiance.

Turquine looked up at her and laughed, mocking her, walking to the table where a large flagon of warm ale waited for him. He took a drink and looked at her; she could see him assessing her. She could be formidable foe, she knew, just as she knew she’d never be broken — not by him, or any man — which was why she knew Grummer would never break.

And he hadn’t; he’d been held captive for almost two weeks now, Turquine told her.

Grummer’s latest feat had been the construction of the wall. It was supposed to have lasted ten days, so Turquine could show his captors to his buyer; Grummer did it himself in under four days. Turquine was livid, which was why he had taken his frustration out on her, she knew.

A part of her understood that about him. Turquine could be stubborn, a man set in his ways; a little too unpredictable. She told him it was only a matter of time before the captives rose up against him. All that was needed was a leader, she thought, and Grummer of all people, had proven to be that man.

There was a sense of pride in knowing that Grummer had come from Beyond-the-Wall, but that was as far as it went. Grummer would have to be killed because of the threat he posed to her plans against the throne. It was all political, and she knew Turquine would never understand — or that he himself would be sacrificed as a pawn in her desperate bid for power. Had Turquine listened and raided the surrounding countryside, using peasants to help him with the construction of his Keep, instead of Knights, things wouldn’t have gotten so far out of hand.

It wasn’t something she would’ve advised, capturing Bachelor Knights, or those out Questing in the name of the King, but Turquine wasn’t a man to be dissuaded by sense, or reason, was he? She told him it was only a matter of time before some rogue Knight showed up in search of a kinsman — or two.

And what if that rogue is Lancelot? You don’t have to be a Druid, to see that, she told herself — not with both Lionel and Ector held captive.

It was bad enough knowing there were two dozen Knights being held, but it was worse knowing that her nephews were somehow involved. It was more than just a little distressing. It wasn’t something she wanted to delve into too deeply, but knowing Agravaine and Modred were involved had been enough to make her pay attention. The fact they’d made the effort to capture Grummer — for their own reasons — was more than a little curious, though.

What could their reasoning be? she wondered.

She had no desire to be here, not now, not having discovered that Lancelot’s kin were held captive. But on her way to Camelot to celebrate the Tournament of Youth, Morgana had made the mistake of agreeing to ride with Accolon the Gaul, as well as his Saxon followers.

They’d journeyed across the channel to raid smaller holdings inland, and he’d sent word to her. They needed slaves to sell to the flesh merchants in Damascus, he’d said, and there were riches he was willing to shower her with, if only she’d agree to meet with him. And she had. It was foolishness on her part, and she knew it; so many things could go wrong. But that womanly need of hers — unsatisfied by her own husband’s shortcomings — cried out for him, and wouldn’t be denied. She could picture herself on her back, her creamy thighs spread wide, and Accolon thrusting himself into her.

She balked, startled to see Accolon and his Saxon horde cresting the low lying hills in the distance. Eventually, she’d count five women among them, and wondered what small town, or hamlet, they’d ravaged along the way? Did it matter? she asked herself. The women would eventually be cast into the dungeon with the others. How many was that Turquine said? Almost a dozen women? And two dozen Knights? The women were bound for a better life he’d said, rather than a life of penury and squalor the Knights would find themselves in. The women would be sent to eager husbands, or maybe even a harem — if they proved pretty enough — or if they had the gold coloured hair so highly desired — while the Knights would find themselves condemned to the galleys.

And how is that a better life? she asked herself. Only a man would think a life in wanton servitude is what every woman secretly wants.

The women would be raped — if they hadn’t been already. Those that were too old, would be put to work in the fields, or would serve as scullery maids in dark kitchens, or perhaps serve in a whorehouse in the outlying areas. It wasn’t a life she’d wish on her worst enemy — not even the Queen. She was well aware that she might’ve suffered the ignominy of such a life herself, had she not been half-sister to the King, and wed to Urien, both a king himself and a trusted ally of Arthur.

If Lot had proven himself victorious during the War of the Twelve Kings, life would’ve been very different indeed, she told herself.

She made her way down the thick-slabbed cedar steps of the Keep, the cold timbered walls seeming to close in around her. She wrapped her arms around herself, breathing in the fresh scented cedars as she hurried down the stairs. Two servants standing at the doors of the Great Hall pulled them open for her as she approached, stepping outside and feeling the bite of cold air cutting through her.

She waited as Turquine appeared, coming out of the stable and standing beside her. Sliding an arm around her waist, he buried his face in the volume of hair that fell about her shoulders and down her back. She could feel his hot breath on her neck and smiled.

The bridge fell with a hollow echo that vibrated through her feet.

“It’s the Gaul, Accolon,” Turquine said, sounding curious. “He’s early.”

“Ye were nae expectin’ him, my Lord?”

“I’d ‘eard it noised about some that ‘e an’ ‘is Saxons were out an’ about, but one canna put too much stock in such tales, eh?”

“An’ yet, here he is,” she said, a shudder of anticipation running through her body.

“Are ye cold, Lady?” Turquine asked, looking down at her. She nodded and he threw the great bearskin cape he was wearing around her narrow shoulders. The cloak stank of wood smoke, and musk — the damp of a thousand days gone — but it was warm and smothered her in its grip.

Accolon and his Saxons entered the courtyard — laughing, and jovial — in high spirits with the fresh memory of a well-fought mêlée coursing through their veins. Three of the women had been defiled, their breasts laid bare through torn bodices, the flesh beneath bruised by rough hands. One woman’s fleshy thighs were exposed as she screamed.

As the riders entered the courtyard they paused long enough to stare at the stately figure of Morgana, her long-flowing hair a dark mantle framing her face where the large bearskin cape enveloped her like a mane. The women were tossed to the ground without a thought, the Saxons quick to follow — one of the woman was dragged away screaming with four men ripping at her clothing — the other women quickly parcelled off.

“Accolon! Ye surly bastard!” Turquine laughed, strutting forward as the Knight pulled up on the reins and dumped Gwenellyn to the ground. She fell hard, and Morgana moved to help the girl up.

“Leave off, there!” the Knight screamed at Morgana, his language a guttural mix of Anglo, Saxon, Gael, and Celtic, as he jumped off his horse. “She’s a right proper bitch, that one. Bit me, she did. Twice!” he added, showing both Turquine and Morgana the purple welt on his hand.

“No doubt well earned!” Turquine laughed.

“An’ wherefore, eh? If not fer havin’ been forcibly ta’en from hearth an’ ‘ome, I mean t’ say, the poor bairn,” Morgana sneered, ignoring the two men and helping Gwenellyn to her feet. She took the bearskin cape off and draped it over the girl’s shoulders. “The gods cursed ye the day ye were first born, Accolon; but may they strike ye down if you’ve ta’en her virtue,” she added.

“Taken her virtue?” the Knight laughed. “Oh no, my Lady. Not I! I know the value of a woman’s beauty. She’s the best of the lot, she is! Just look at her,” he said to Turquine. “Young, an’ headstrong. But have you e’er seen such beauty? Aside from your own, dear Lady? Nae!” he said loudly, his voice echoing through the close confines of the courtyard. “I’ll nae let any man near her. Her beauty alone is worth a fortune, but her virtue? That’s worth a king’s ransom!”

“An’ what would ye know of a woman’s virtue?” Turquine laughed. “A real man cares little for a woman’s virtue; his only need is that she give him sons!”

“Maybe here, Turquine, but the Saracens hold virtue in a woman beyond reproach,” Accolon said. He walked toward her, looking at her wrapped in the great bear cape. She refused to look at him, and he laughed, reaching for her hair.

“Too bad she’s a raven-haired bitch,” he said with a shake of his head. He looked up, and Morgana thought he had his audience now. Turquine was drawn in by every word and gesture.

“Those blue eyes? Aye! Like sapphires, they are! Look at them!” He grabbed her by the chin and she stared at him, refusing to bend. “Aye. An’ worth as much, too. A month’s worth of prayers and Pater Nosters by yer monks, ye can be sure! And her skin? Unblemished! Golden haired women do fetch in more gold, but beauty always pays a high price.”

“An’ if I keep her as m’ han’maid?” Morgana asked, watching as Gwenellyn turned to her with a quizzical knit of her brows. The girl was standing up for herself and refusing to be cowed by Accolon, and Morgana liked that about her, but she was frightened half to death, and Morgana could see that as well. She refused to let the fear show, which made Morgana think she was a girl who could be grateful. And a grateful girl would do anything. She lifted Gwenellyn’s chin and stared at her, shaking her head at the sight of such rare beauty.

Accolon’s right about that, she told herself.

Morgana opened the bearskin cape and looked at the fine embroidery on the gown Gwenellyn was wearing; took in her silken slippers, and saw the ripped bodice and how the girl tried to cover herself. Staring hard at Accolon, Morgana pulled the cape closed.

“Is she not pleasing, my Lady?” he smiled.

“An’ ye claim ye ne’er took her virtue?” Morgana said.

“Of course I thought about it!” the Knight grinned, looking at Turquine. He reached over, pulled the cape down, and ripped at the already torn bodice of her dress, exposing Gwenellyn’s breasts.

“Just look at those teats! Young and firm. Eh? What’d I say? Not like these other bitches here, with their suckling brats all but hanging off of them. No. Young and firm, I say!”

“Enough!” Morgana said, pushing Accolon aside and pulling the bearskin cape up, securing it in place with a broach. “Yer name, child?” she asked, her tone gentle. She kept a wary eye on Accolon, and watched Turquine as he undid the small catch of his scabbard.

“Gwenellyn.”

“An’ where were ye to, Gwenellyn, yerself with all yer finery?”

“On the road to Camelot.”

“Camelot?” she echoed. “The very place I meself am goin’!” she laughed, and the girl looked up at her. “An’ wherefore would ye be travelin’ to Camelot?” Morgana asked. “An’ with whom?”

“It was my uncle’s hope to find me a husband.”

“A husband? How old are ye, child?”

“Sixteen years this past spring.”

“Ha! See? Old enough!” Accolon declared.

“An’ are ye pilgrims perhaps?” Morgana asked.

Gwenellyn shook her head.

“Oh? Moneyed perhaps? A wealthy merchant, or maybe a Lord?” Accolon asked in anticipation of more riches. He grinned a grimace and Morgana silenced hm with a look.

“There are no riches, as my mother is widowed,” she said with a note of defiance that brought a smile to Morgana’s thin lips.

“But ye have kin?” Turquine asked. “An uncle, ye say?”

“I do.”

“There! You see? She’s not worth anything to them,” Accolon said, as if his point had been made.

Morgana looked at him once more and the man fell silent.

“There is more.”

“There is no more. Her mother is widowed,” Accolon said. “She said it herself.”

“An’ yer uncle, child?” Morgana asked.

“Pellinore.”

“As in, King Pellinore?” Turquine asked, his hand resting on the hilt of his sword.

Gwenellyn nodded.

“Which makes ye kin to Lamorak an’ Percival?” Morgana said.

“They call me sister,” she replied.

Morgana turned to look at Accolon, who appeared non-plussed; she looked at Turquine, who paled at the mention of Lamorak’s name.

“Ye’ve bandied about with King Pellinore’s train? An’ ye’ve brought yer Saxon horde here? To my Keep?” Turquine said. “Are ye mad?”

“Pellinore’s an old man. What good will it do him to know we’re here? I’ve fifty Saxons with me.”

“Not Pellinore, ye fool! His sons! Oh, but ye have fifty Saxons! Ye think fifty Saxons’ll stand against such as ‘em?” Turquine laughed. “ It’s Lamorak de-fuckin’-Gales! The greatest knight alive — after Lancelot. An’ if it’s not ‘im, it’s ‘is fuckin’ God-lovin’ brother, Percival! He’ll kill ye just as quick, but he’ll pray for yer blackened soul, an ‘e does! Ye’ve brought ruin down on us all!”

“And you think Lamorak will attack this Keep? Are you mad? One man against a Keep?” Accolon scoffed.

“A Keep, aye,” Turquine said with a slow smile. “A man like Lamorak at the gate? What d’ ye think ‘e’ll do?”

“What can he do? Nothing!”

“Nothin’? ‘e’ll burn the place t’ the ground an’ kill ever’ man, woman, an’ child what comes runnin’ out. All that t’ get what ‘e wants. If that what ‘e wants is ‘er? ‘e’ll take ‘er from ye an’ smile at ye as ‘e slits yer gullet open. The man does enjoy his killin’. Now get yer thievin’, rapin’, Saxon scum off my women.”

“You want me to tell my Saxons that they’re fuckin’ your women! You expect that will hold them back? We made a deal, ye rat-bastard. Leave off with that thinking they belong to you. I took ‘em on the road — ye heard the girl — fair and square as ye say. I left the villages. You give me the Knights you’ve captured — as you said — and whatever other women you may have, and I’ll pay you a fair price. Whatever women, or captives, I bring along with me, are no concern of yours.”

“And the girl?” Morgana asked. “Pellinore’s kinswoman? What of her?”

“What of her! She’s not yours, dear Lady, to say what will, or will not, be done with her. She’s my property! Nothing more than chattel! I say what will be done with her. If I want to take her virtue, I will. There’s no one here that will stop me.”

“No! Ye dinna have that choice!” Morgana said, stepping toward the man and looking down at him. “She’s Pellinore’s niece! ‘e’s not just any king! Pellinore could well ha’ been standing in Arthur’s place, but for ‘is foolish loyalty to m’ brother. She’s not chattel to be bargained for.”

“And you are in no place to say me yeah, or nae, Lady,” Accolon said, his voice low and threatening.

“Think ye not?” Turquine said, the point of his sword pressing against Accolon’s back.

“I’ve killed better men than you, Turquine,” Accolon said over his shoulder.

“I don’t doubt ye have. But not today,” he said, and stepping forward pushed the sword’s length through the man’s body.

“What have ye done!” Morgana screamed at him.

“I’ll not have such a man as ‘im threatenin’ ye, m’ Lady,” Turquine said, pushing Accolon’s body off the length of his sword with his foot. He watched the man fall to his knees, the blood bubbling up from his lips as Accolon gasped for a last breath he was unable to find.

“An’ what of the Saxons?”

“That new Curtain Wall yer Pictish bastard put up last week?” he smiled, looking at it. “’Tis a grand place to hide a man with a longbow.”

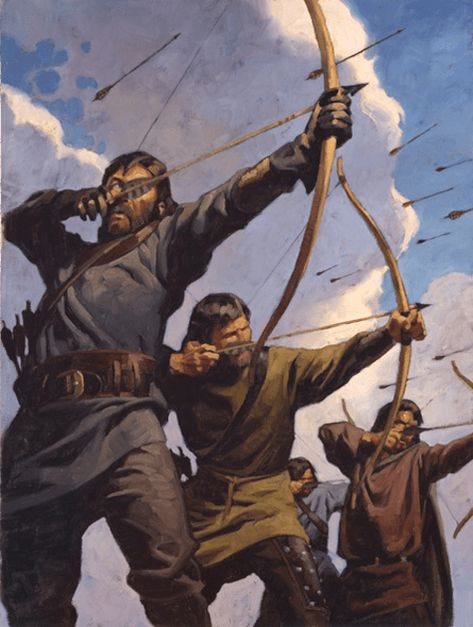

He raised an arm and three score of archers stood up, bows taut, barbed arrows shining in the sun. He looked at Morgana and smiled, then looked at the wall where his Master-at-Arms stood waiting. He dropped his arm and the arrows split the air.

Turquine, Accolon, Morgana - I don't want to even be part of the same species as these characters. All three seem to be absolute monsters with no redeeming value. Great writing, my friend, but bring me a hero, for god's sake! ha ha ha! I am still fascinated by the incongruity of the beautiful images you find to illustrate this violence.