Just so you know, we’re almost finished with the FREE ‘Stacks for THE SHIELD OF LOCKSLEY. All of PART TWO is ready to go up, and, as you know, will be behind the PAYWALL for my 25 PAID subscribers to enjoy. I’m thinking the entire novel will be about 250,000 words, which is about 500 pages here, (probably closer to 800 pages in a store-bought book).

ANYWAY, our story so far…

Locksley is confronted by the strange sight of Palomides and his Immortals, four Men-at-Arms, as well as a Squire, and thinks they are under attack. He sounds the alarm and rushes to prepare for battle…

CHAPTER 9

THE KNIGHT’S SQUIRE

Locksley spurred his horse through the thickening trail, the branches whipping at him with relentless vigour as he ducked down, trying to avoid being unhorsed by a low lying limb. He used his shield as he reached up and dropped his visor down, telling himself all he needed now was to be slapped in the face by a branch. It was one of the first things Grummer told him when he’d served as his Squire. But still, even as he felt the excitement of the chase building within him, and his heart racing in his breast, he reminded himself not to get distracted. He could see the rider ahead of him; he could sense the distance closing — he could even see the man looking over his shoulder as he spurred his horse on recklessly.

The trail was a muddy course with all the rain that had fallen over the last three days, and Locksley feared his horse might slip, or take a tumble. He worried that every puddle the horse raced through might hide a hole that would snap the poor animal’s leg. He had no way of knowing how far they’d ridden from the field and their attackers, and a part of him wondered if bolting off as he had was a mistake. He wondered where the other rider had gone off to. A part of him was thinking the man was either behind him, or perhaps had taken a different trail and was now lying in wait for him.

He tried to keep the spear he was carrying off the ground; the effort needed to keep the tip from dropping and catching a mound of earth was playing on his mind. There were so many things that could go wrong, he told himself. But it seemed the trees were slowly thinning, the fir trees giving way to open ground, replaced by thinner birch trees, and aspens. There were willow trees that lined the course of the lane, their tentacled branches whipping in the gentle wind, their gnarled, intertwined, and twisted trunks looking like something out of a nightmare dreamscape.

He slowed as he came into the opening. The grass was long, the trail lost somewhere inside of it. He could see the path the rider and his horse had taken, then lifted his visor and looked across the field. The sun broke through the clouds and he could see it reflecting off a large pool of water. The wind rippled across the surface of the water; the trees bowing low as the wind sloughed through the small glade.

He saw a figure on the other side of the pool stepping out of the woods, carrying a brace of rabbits as well as four grouse. The sun broke through the trees and the man saw him, waved, and made his way toward him, walking through the pool of water which was up to his knees.

It was Brennis.

“Well, if it isn’t the Beggar’s Knave!” he called out with a laugh. “Out and about are you, Sir Knight? I was on my way back,” the Squire called out from the middle of the pool. He lifted the morning’s catch, smiling broadly. “I found some eggs, as well.”

“Did ye see ‘im?” Locksley asked, looking at the surrounding woods, reining his horse in tight. He wanted to be ready to dash off at a moment’s notice.

“See who?” Brennis replied, suddenly alert that something was wrong.

“That bastard horse an’ rider?”

Brennis shook his head. “I heard him,” he said. “Why?”

“The Orkneys attacked us, and Geoffrey’s taken an arrow.”

“How bad is it?”

“I dinna can.”

“I can tell you right now, whatever you’re thinking of doing, don’t,” Brennis said, shaking his head as he reached the edge of the pool.

“I canna let ‘im escape,” Locksley said. He’d set about on his own little quest hoping to charge the man down, and meant to follow through.

“You can’t go into those woods not knowing what’s waiting for you. If there’s one thing I’ve learned living in a brothel, it’s don’t go into the woods alone.”

“And where did you hear that?” Locksley scoffed.

“From every Knight that’s ever been ambushed, or taken prisoner. They all show up at the Lion eventually, with stories meant to impress their companions.”

“Ye make it sound like it’s an ever’day doin’.”

“Isn’t it?”

Locksley was distracted by a flash of light and looked into the distance. where he saw someone standing on the other side of the pool. He thought it might be a woman, but dismissed the idea. Why would a woman be in the middle of a forest alone? The more he looked at the figure, the more he thought there was something familiar.

“There’s someone there,” he said, pointing; Brennis turned to look.

Brennis shielded his eyes. “It’s the woman that left last night.”

“What’s she doin’ out ‘ere?”

Brennis shook his head as he stared into the distance.

There was a sudden crash in the woods as the Orkney Squire came out of the trees with the other rider. Locksley dropped his visor down into place and pulled his shield up. Brennis dropped the rabbits and birds, and then placed the eggs down carefully as he notched an arrow in his bow. He drew the arrow back as the two horsemen worked their horses into a gallop. The water splashed about them, the droplets cascading over them in the sunlight — each droplet a colourful prism that caught the light — as Locksley levelled his spear and spurred his horse forward.

Brennis released the arrow and the nearest of the two riders fell, clutching at the feathered barb sticking out of his throat. At the same time, Locksley caught the Squire with his spear, hitting the centre of his shield. The force of the attack caused the Squire to shift in his saddle, the spear sliding against his shield bending, shattering, and finally piercing the man’s chest. The man’s horse rose up on his hind legs and the Squire fell into the water, a stain of red blossoming about him as Brennis reached out to grab the frightened horse.

Brennis walked through the water to where the first man lay, and grabbing the arrow, wrenched it free, tearing the flesh open. He rinsed the tip of the arrow in the water before returning it to his quiver. Then he bent over and searched the man’s body, taking what few coins he could find. He stood up, counting the coins, and then looked up at the woman who was approaching.

“Who are you?”

“I’ve come to speak with you…Breunor,” she said with a smile.

“My name’s Brennis.”

“That’s what people call you, but you know, and I know, that’s not your real name.”

“How do you know that?” he asked, putting the coins he found on the man’s body into the small pouch he carried under his tunic. He dropped the tunic down and looked at the woman, waiting for her to answer.

“I know a great deal about you. I was well acquainted of your father —”

“My father? He was a great king, foully slain.”

“Yes, foully slain, but he was no King,” she said. “He was a Knight. Do you still have his coat?”

“How do you know about my coat?” Brennis nodded.

“From this moment hence, I want you to wear it as a talisman,” the woman said.

“And why would I do that? It’s all cut up and bloodied. It needs to be cleaned and stitched. I don’t supposed you’ll be doing that for me?”

“Wear it, and you shall have your revenge,” she laughed.

“And what revenge would that be?”

“Only by wearing that coat, will you find your father’s killer.”

“And why would I believe that?”

“Believe me or not, it’s up to you,” she said, and he watched her turn away, her body suddenly becoming transparent as she walked into the water, her body melting.

“Wait! You can’t just…leave.”

*

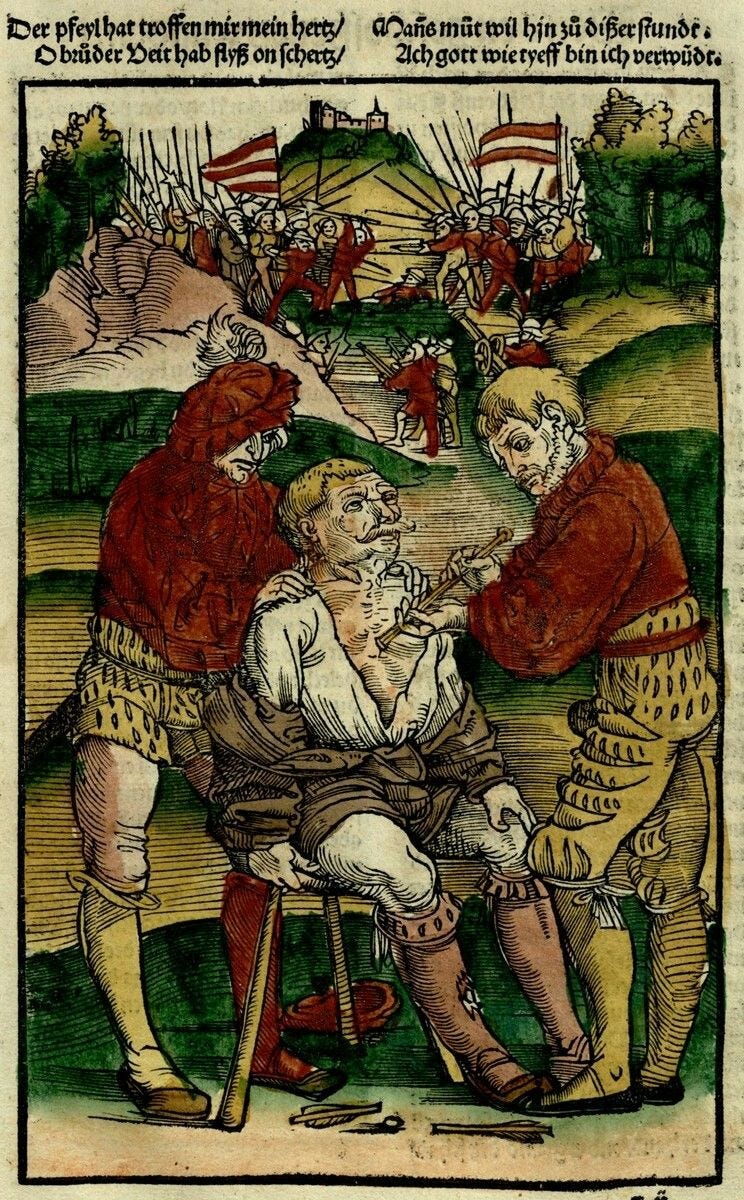

“You have to hit it with the flat of your sword,” Vergil said, looking at Lamorak. “Hard.”

“Yes, you said that,” Lamorak replied.

“That’s because the arrow’s pressed up against the bone,” and here he held his index finger against the fingers of his left hand. He pushed and the finger slipped naturally between the fingers of his left hand. “Hopefully, it turns, and slips between the bones and the muscle,” Vergil was saying.

“Hopefully?” Lamorak said, sounding dubious.

“A lot can go wrong — it most likely will — but what choice do we have?”

“How hard do I have to hit it?” Lamorak asked.

“Hard,” Palomides said, looking at Godfrey, who nodded. “You’ll probably pass out from the pain. Let us pray that you do. It will make what has to come after, a lot easier for all of us.”

“I just want you to know, I’m not looking forward to this,” Godfrey said, the pain written on his face and echoing through his words.

“Let’s get this over with,” Lamorak said, picking up his sword.

“Wait!” Palomides said, and walking to one of the bags on the smaller pack horse, came back with a wooden bound book, three fingers deep. “Put this against the arrow. That way, you won’t miss.”

“What if the arrow goes through the book?”

“If you hit it hard enough, it shouldn’t matter.”

“That doesn’t sound too promising,” Godfrey said, struggling against the pain.

“Don’t talk. Ty not to think about it,” Palomides said, holding the book a fraction away from the arrow and looking up at Lamorak. He nodded. Mustafa the Immortal held the other half of the book, helping to steady it as Lamorak raised the sword and swung.

Hard.

Godfrey gasped, and screamed, as the arrow inside his body cavity snapped, the arrow head pressing against the bones and the barbed tip sticking out fractionally, as the arrow’s shaft slipped partially out through the bones above the arrow’s tip. A slow streak of blood dribbled from the new wound, and then started to flow.

“That doesn’t look good,” Vergil said softly.

“What happened?” Lamorak asked.

“The arrow snapped,” Palomides said.

“Snapped? How?”

“It was probably damaged before it was released,” Palomides said, pulling Godfrey back and looking at the wound. He shook his head at the sight.

“Do I hit it again?” Lamorak asked.

Palomides shook his head.

“It still has to come out,” Vergil said.

Mustafa said something to Palomides and the man nodded.

“He says he will pull it out.”

“Pull it out? How?” Vergil asked. “What are you going to pull it out with?”

“We have tools for that,” Palomides said.

He called out to Amal, the second Immortal, who was quick to run to one of the other pack animals and returned with a long leather roll-up pouch. Mustafa untied the pouch and spread it out on the grass in front of him. There were several varieties of instruments, from scalpels, scissors, pliers, and tongs, to vials of potions and lotions, astringents, and unguents. He said something to Amal and the Immortal ran through the water to the forest’s edge.

“Where’s he going?” Lamorak asked.

“We need to make a poultice,” Palomides said.

Mustafa reached for a scalpel, testing its weight before slicing the flesh around the arrow without warning. The blood flowed quick. He dropped the scalpel and selected a slender pair of pliers he was able to force around the arrowhead, pulling it out in one quick motion. The arrow came out with a section of splintered shaft behind it.

“What about the rest of it?” Lamorak asked.

“It has to come out,” Palomides said. “We cannot leave it inside the body cavity.”

“How do we get it out?”

“He must dig,” Palomides said, and Lamorak made a face, thinking of the pain.

“You can’t know where to dig,” he said.

“What do you suggest?” Palomides asked.

“Pull it out through his back. The barb’s not there. It should come out easily enough.”

“Nothing is ever as easy as you think it should be,” Palomides said. “If you pull it out, it may kill him.”

“Either way, it has to come out. How do you expect to pull it out of his chest? The arrow’s split. To be honest, I don’t think it matters if you pull it out from the front, or the back, he probably won’t last the fuckin’ night.”

“If the arrow is split, I might leave a sliver inside.”

“We have to do something,” Lamorak said. “We can’t just leave it there. He’ll bleed to death. If you pull it out from the back, maybe whatever’s in there, will slide back into place? There’s a lot of stuff inside.”

“Yes.”

“If you pull it out from the front — not knowing where the shaft is split — it could be worse. I’ve seen a lot of arrow wounds. I say, pull the arrow out, cauterize the wounds, and pray to that demon God of yours that he lives.”

“From the back?” Palomides said, and leaning Godfrey forward could see the tiny piece of wood still sticking out of the man’s back.

Palomides looked at Mustafa and said something. The man nodded and sorted through various instruments in the pouch. Satisfied, Mustafa looked at the wound; rubbing his bloodied fingers along the wound, he nodded. He reached into the rolled-out pouch and took out a long slender rod with a thin, silver thread. There was a small loop at the end of the silver thread and he was able to slide it into the wound about a finger’s length down the shaft. He pulled on the thread and felt Godfrey call out, his voice a muted cry of pain.

“It must be done quick,” Palomides said. “As soon as it is pulled clear, hold the knife above the would and count to five before placing it on the flesh itself.”

Lamorak nodded.

“Do it.”

Locksley and Brennis rode into the camp with a second horse in time to see Mustafa pull the arrow out of Godfrey’s back. It was a sickening red length as long as a man’s forearm and as thick as a finger. He tossed it to the side, and Palomides picked it up, rinsing it with water and looking at it closely as Mustafa held his hand on the wound. He was pressing hard. Palomides ran his fingers along the bloody shaft and Mustafa looked at him. He nodded his head and Mustafa turned his attention back to Godfrey’s wounds.

“Is the knife ready?” Palomides asked Lamorak.

“What are you doing?” Locksley asked, jumping from his saddle with a practiced ease.

“Cauterizing the wound, I’m told,” Lamorak said, watching the knives where they rested in the embers.

“To be honest, we’ll be cauterizing two,” Palomides said. “And remember Lam, the one in the front is far more worrisome than this one.”

“Just tell me where to lay this,” Lamorak said.

“Here!”

Mustafa lifted his hand, drew a circle in the blood on Godfrey’s back, and raised his hands out of the way as Lamorak held the red hot blade over the wound, his lips moving as he counted before pressing the blade down.

“And press hard. Lean into it,” Palomides said, looking at the second blade.

He was on his knees sorting through the little glass vials. He pulled three of them out of the pouch and made a thick paste using a small vial of what looked like regular water.

“What’s that?” Lamorak asked, feeling the heat of the blade and trying not to inhale the stench of the burning flesh.

“Virgins’ tears.”

“No such thing.”

Lamorak looked up as Amal returned, holding a large clot of mud and herbs in his hands. Mustafa said something and Amal placed the mud clot on the ground, taking two clean pieces of silk from a pocket somewhere in the pouch. He dug his hands into the ooze, laid it on the first cloth, then tied the four corners closed and repeated the same process with the other one. When he was done, he had two pouches about the size of a man’s palm.

Lamorak pressed on the blade, and the slow, lazy tendrils of burning flesh invaded his senses as he grimaced, holding his breath until the blade gave up its heat. Mustafa spread the paste on the burned flesh, and placed another clean rag over the paste.

“His chest! Quick!” Palomides said, and Lamorak helped lay Godfrey on his side. Mustafa placed the poultice against Godfrey’s back, and rolled him over, hoping the man wouldn’t move too much. Lamorak grabbed the second knife and looked at Mustafa.

“The same,” the man said, and Lamorak nodded.

Lamorak stood above Geoffrey, looking down at the man’s crushed leg, and the bone sticking out below his knee. Geoffrey looked up and tried to smile. Lamorak could see it hurt just for the man to breathe. He could understand that kind of pain, he reminded himself. They’d all of them had at least one life threatening injury over the last years, the kind of injury where your mother is on your mind and you wonder if you’ll ever see her again.

“It has to come off,” Palomides said, looking at Lamorak.

“Don’t tell me,” Lamorak smiled. “And to be honest, I think Geoffrey already knows. Any bone sticking out like that would probably be a pretty good indicator. Anytime I’ve ever seen a bone sticking up like that, the man’s lost his leg. I think he knows.”

“He’s going to need a drink,” Palomides said.

“Just one?” Lamorak laughed, giving his sword to Vergil. “See if you can get a fine line on that, will you? I don’t want to have to do it more than once. No man deserves that,” he added.

*

Locksley stood transfixed as Lamorak stood off to the side, resting the large blade on his shoulder as he waited for Geoffrey to take one last swallow of the whiskey Palomides had hidden in his saddle bag. He’d tested the blade with his thumb and nodded his silent approval.

“Are you ready?” Lamorak asked Mustafa. The man sat on one side of Geoffrey, holding him down; Amal sat on the other side.

Locksley listened to the blood curdling scream as Lamorak swung the sword with all his weight behind it. There was a sickening, bone-crunching snap, and Palomides pulled the severed leg out of the way as he doused the last of the whiskey on the stump of flesh and ignited it. He picked up the broadsword resting in the embers and sealed the wound. Mustafa was there at the same moment, smearing the mysterious paste on the leg, before wrapping it tight with a bolt of silk.

“We can’t take them with us,” Lamorak said. “We’ll have to find some place safe to leave them.”

Gruesome but realistic. Not only was the medical practice primitive at the time, the forest and wet conditions made it all the worse. Very good exposition. Thanks!

Oh I am excited to read this - always interesting to see historic medical action!!