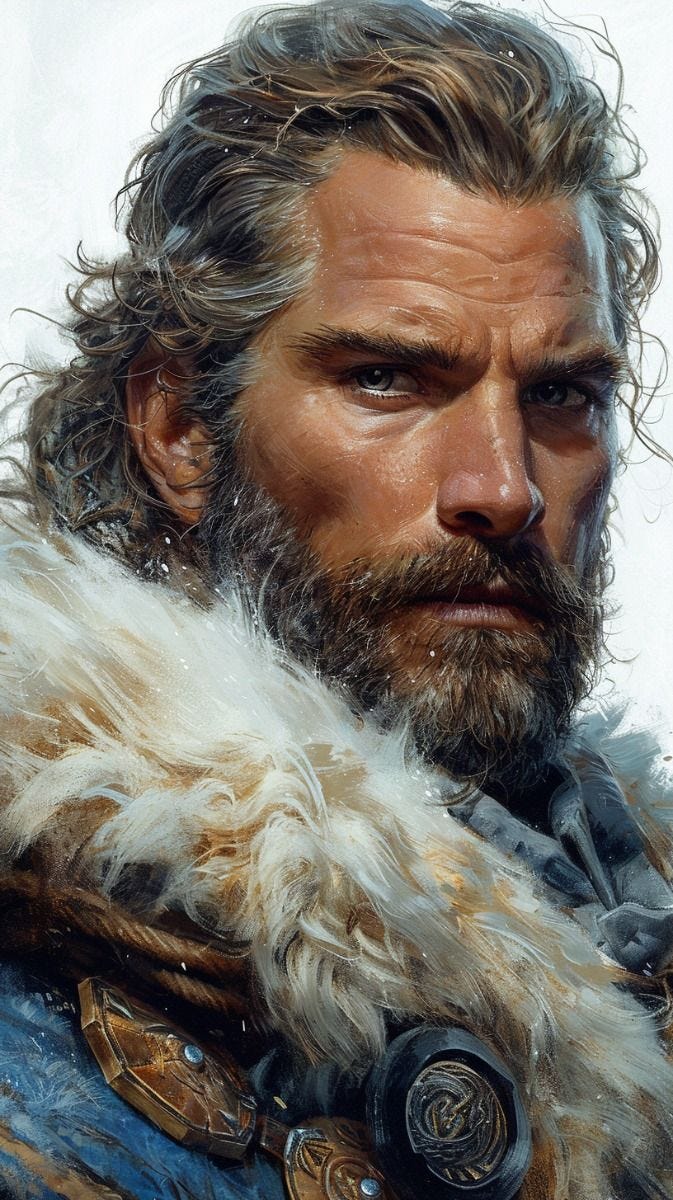

The story so far…

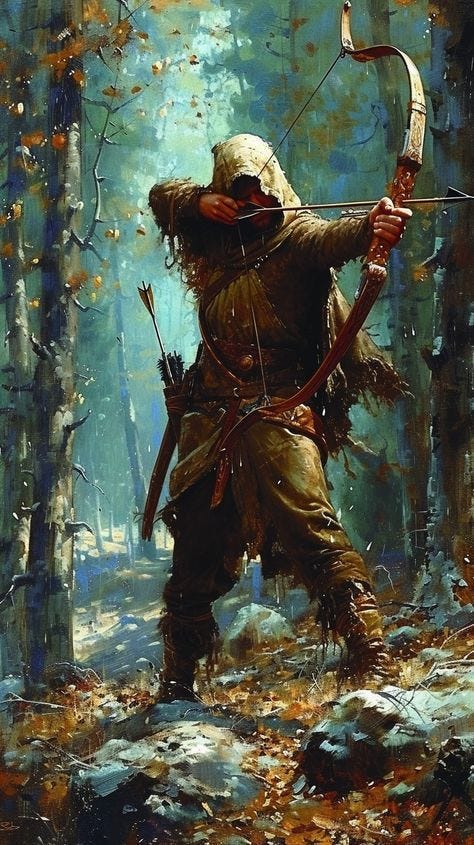

Locksley takes off in mad pursuit of the two Squires and follows them in the forest where he comes across Brennis who has been hunting. At the same time, the two squires show up and while Brennis kills one with an arrow, Locksley spears the other one.

As Brennis goes to search the dead bodies for whatever coins he can find, he see the Lady of the Lake emerge from a large puddle and tells him he has to wear his father’s coat if he expects to avenge his father’s murder. And as quickly as she shows up, she disappears.

In the meantime Lamorak, Palomides, and The Immortals, are trying to save The Boys. Godfrey has an arrow in his back, and Geoffrey loses his leg through some good old fashioned field medicine…

Just to warn you, this is long.

THE CASTLE IS A KEEP

Grummer felt the wagon dip into a hole and braced himself as another jolt rocked the cart. Ector groaned, rolled over, and pretended to go back to sleep. Grummer, thinking Ector really was asleep, shook his head in wonder. He drew his knees up, trying to get comfortable, and remembered the chain’s length just as he reached the chain’s limit. He cursed when he felt the shackles dig into his ankles — not as bad as it had been that first day — but bad enough to rip some of the wounds open.

Ector opened an eye.

“You made it bleed,” he said dryly.

“I trust ye slept well?” Grummer asked, fighting a grimace, and shuffling closer to the chain.

“I’d be lying if I said I’ve had better fitting beds,” Ector added, forcing a smile.

“Aye, that I can ye,” Grummer said, struggling to sit up. He looked down at his feet and cursed Turquine for taking his boots. It made perfect sense now, didn’t it? Any pain that had been inflicted, had been his own doing. He could see the length of wound that had been ripped away; the fresh blood oozing more than flowing, which he supposed was a good sign. He knew from experience that he could be in for a lot of trouble. He’d think himself lucky if he could still walk in three days time.

Grummer looked up as the once familiar sight of Turquine’s stronghold came into view.

“It’s changed since last I’ve been ‘ere,” Grummer said, looking between the pickets holding the wagon’s rails in place. The sun baked the sides of the castle walls, and the half-built spire that loomed above it all. The once narrow moat had been expanded, its width twice the size of what it once was.

“You’ve been here before?” Ector asked. “Why wouldn’t you tell me that?”

“To what end? ’Twas nae more than a Keep then,” Grummer explained.

“A Keep? Is that why you never thought to mention it? Because it was a Keep, and not the castle it so obviously is now? Is it true Turquine?” Ector called out. “Has Grummer been here before?

“Fuck off,” Turquine called back.

“I said has Grummer been here before?” Ector repeated.

“And I said to fuck off,” the Knight repeated.

“I don’t even know what I’m supposed to say to that,” Ector said, looking at Grummer. “What am I supposed to say to that? Am I supposed to tell him to fuck off as well?”

“Ye doan have t’ say anythin’.”

“I’m sure you’ve heard the rumours,” Ector said. “About how he’s been building this thing for years now?”

“Aye.”

“And what? Do you think he plans to do the same with us, then?”

The forest had been burned and hacked to pieces since the last time Grummer remembered having come here; it had been a blemish against the landscape. All he could think of was that everything around the keep was buried in mud. But the mud had been used in making the plaster, which covered the logs and gave the Keep the appearance of having been built of stone. He’d heard that when the autumn rains came, the place was a cesspool. In the summer months it seemed that there were endless dust storms. The sand and grit would get into everything.

That was when he remembered who had told him. It had been a whore in one of the town’s brothels. She told him that the moat — which had been little more than a ditch back then — still flooded every Spring. The heavy rains flooded the hills she’d explained, and joining the streams and creeks, overflowed and flooded the banks of the moat, allowing the crops to thrive; flowers flooded the yards and the Keep was soon a castle.

The stumps had been cleaned up and burned a long time ago, Grummer could see. After the cones and branches littering the ground were thrown on the flames, a blue cloud of thick smoke had hung over the Vally for three years, she’d said. And all the while Turquine carved out more land to make room for further expansion. Seeing the original keep, Grummer remembered the challenge issued by Bedivere as to which of them would unhorse the Knight first. Grummer knew he’d have never accepted the challenge had it not been for the wine. But he had — both of them had — which was why Bedivere told him to answer the challenge first.

Things didn’t go well for him that day, he was ashamed to remember. Turquine unhorsed him on the first pass, and then, forcing his large warhorse to a stop — and almost sliding on the sod-slick grass — Turquine had his sword out before Grummer even made it to his feet. He distinctly remembered the pain of a broken rib, or maybe it was cracked? It didn’t matter, it hurt just the same. But he also remembered stumbling to the ground just as Turquine’s blade sliced the air over his head. And then Turquine reared his horse up and brought it around to face him, the hooves lashing out at Grummer’s face, both of the hooves sheathed with steel flashing in the afternoon light.

Bedivere came in from the side and Turquine went down with his horse. Bedivere’s lance had caught the horse under the saddle at the very moment Turquine made it rear up and attack Grummer. The lance pierced the horse’s side, and splintered. He still remembered the horse’s scream of pain. The momentum had knocked both horse and rider to the ground, shattering Turquine’s leg. Grummer had been indebted to Bedivere ever since. He wondered if Turquine remembered the events of that day in the same way.

That Turquine’s stronghold had once upon a time been a single Keep, mattered little now. A square tower made of timbers and wood, and rising high above the trees, gave it a clear, unobstructed view of the valley around it. The Keep had been surrounded on all four sides by the shallow moat — not deep enough to even qualify as a moat Grummer remembered, but a ditch, just as the whore had told him. It wasn’t enough to deter an enemy from crossing it, she’d added, but it wasn’t supposed to; it was lined with sharp stakes spaced a foot apart, hidden in the murky shallows of the water.

Now, the sides of the Keep had been plastered with mortar and painted white. It gleamed in the distance behind its massive wall. A wide bridge was lowered and several grooms came out to meet them as Turquine pulled on the reins and stepped off the cart.

“Home at last!” he said, stepping to the back of the cart and opening the small latch that held the gate closed. He reached in and grabbed the chain holding Ector, pulling him out of the cart and dropping him on the ground. He laughed, and then kicked Ector as he tried to sit up. Ector rolled over, holding his ribs.

“You bastard! I’ll have your fucking head for this!” he screamed, and Turquine laughed again, kicking Ector once more, and then again.

“Have my head, will you? Do you think you’re actually going to leave? Either one of you? Who do you think is going to help build me my castle?” He turned and looked at his grooms. “Take this piece of shit filth downstairs, and put him with the others. Both of them!”

He reached in to grab Grummer and pull him out, but Grummer grabbed one of the pickets and Turquine’s grasp failed.

“There’s Nae need for that,” Grummer said.

“No?” Turquine slowly drew his sword and pressed it against Grummer’s throat. “How’s this then?”

“I’ll see ye dead,” Grummer said in a low voice.

“Will you now!” Turquine laughed, and swinging the flat of his sword brought it down against the side of Grummer’s shoulder. The pain was immediate. Turquine reached in and grabbed Grummer’s chains, pulling on them before unlocking him. He grabbed him by the ankle and pulled, dragging Grummer out of the cart and dropping him on the hard ground.

“The fuck you will!” Turquine screamed at him. “Do you see them?” he screamed, pointing to a long line of half-naked men labouring under the sun. “Do you? They were once Knights, just like you two fucks. They’ve all said they’ll see me dead at one time in their lives. Every last one of them! Do you understand? They’re still here, and so am I. But, I’m free, and they’re chained to a wall every night and fed just enough slop to keep them alive for another day. That is what you have to look forward to, you fucks!”

He brought the flat of his sword down on Grummer’s thigh, and Grummer grunted, not wanting the bastard to know how much the blow had hurt. For added measure, Turquine kicked Grummer in the back.

“Now get up! Both of you, or I’ll let my boys use you for target practice. You can never get enough time in when it comes to bow work.”

Grummer struggled to get up, feeling the pain in his thigh where Turquine had brought the sword down. It had felt like a war hammer striking down on his thigh. Ector helped him to his feet, and putting an arm around him, half-carried him.

“Don’t look now, but I just saw Lionel,” he said in a harsh whisper.

“Lionel? Your brother? Why would he be here? Do you think he came out here looking for you?”

“He can’t possibly know we’re here. Besides, it’s not like him to make a decision on his own.”

“No?” Grummer asked. “Why would you say that?”

“He’s always been one to follow me and tag along.”

“So if he’s not out looking for you, who’s he following?”

“Lance. He follows him around like a puppy dog.”

*

As he came up over the rise and out of the trees, Lancelot saw three pavilions on the other side of the clearing. He pulled up under the shade and umbrella-like canopy of a large elm tree. He looked over at Baudwin, his Squire, who had jumped off his horse and was already untying Lancelot’s shield from where it hung off the pack horse. Lancelot was almost certain he recognized two of the pavilions, and shook his head slowly.

“Do you recognize them?” he asked.

“Maybe, if I could read the flags out front.”

The three flags on the pavilions were hanging limp in the gentle breeze, their colours reflected in the huge puddles. Lancelot didn’t recognize the third pavilion and was quick to dismiss it. He was almost positive he recognized the first two.

“Well, I do,” he said.

That’s Grummer and Lamorak, he said to himself, spurring his horse ahead.

The day was warm, the sun having crested the trees long ago, and he wondered why the two of them were still encamped for the day. As he cleared the trees, it became obvious as to what happened; Gawain’s horse lay dead in the middle of one of the large puddles, with four dead men-at-arms scattered around it. Three of the men-at-arms had arrows sticking out of them, and Lance smiled seeing them dead. There was little love lost between himself and the Orkney Knights. The bodies were being stripped by the two Squires, the arms and weapons piled in front of them — Grummer was never one to not take advantage of a situation—and he found himself grinning as he approached the encampment.

He turned to look at Baudwin, but the lad shook his head and shrugged.

“That’s Lam’s ensign, isn’t it?” Lancelot said.

“You would know that more than I, monsieur,” Baudwin replied, his Gallic accent thick and difficult for most people to understand.

“And the other tent?”

Baudwin shook his head.

“I’m thinking it’s that Saracen. Look,” he said, pointing. “Isn’t that his beast behind the pavilion?” Lancelot asked, letting his horse pick its way along the trail.

There was a call of warning, and Lance watched as one of the Saracen’s Immortals stepped into the clearing in front of the three pavilions, followed by the Saracen himself, standing with his scimitar in his hands. The huge blade caught the light, its reflection playing on the surface of the pool in front of him. He swung his weapon through the air, watching as Lance and Baudwin approached the camp, stopping some distance away.

The Immortal had his bow drawn taut, pointed at the two riders, and Lancelot saw another Immortal standing in the shadows of the pavilion, while yet a third man stood on the low rise behind. There was another Squire in the field who had been quick to use the dead horse for cover, and had his longbow pointing at them. Lancelot looked at Baudwin who had an arrow notched in his bow, and shook his head. Baudwin eased back on the arrow, but never released it.

Lancelot waited, watching the two Saracens in front of him, one of whom said something over his shoulder. The middle tent rustled and then the flap opened. Lamorak stepped out of the tent with a Knight Lance didn’t recognize. Lamorak put a hand up to shield his eyes, and then grinned, saying something to the two Saracens.

“What’s this, Lam? Can’t say I know much about the company you’re keeping these days,” he said, looking at the dead horse in the field. “But, those are Orkney colours out there, are they not?” he asked, stepping down from his horse and passing the reins up to Baudwin. He held his hands out to the side.

“Lance!” Lamorak called out, stepping out to meet his friend — laughing — as the two men enfolded each other in their arms. “I see you’ve met Palomides. Have you met Palomides?” Lamorak asked, stepping back and looking at Lance.

“Not that I know of, but I’ve heard rumours and stories about him out of Tintagel; most of them from Tristan while he was at Camelot with Mark’s queen, I might add,” he said with a laugh. He looked at Palomides. “If you’re going to make an enemy, you should think about choosing someone less capable,” he smiled.

“One could say the same for him,” Palomides said, his monotones voice clipped, and the accent making it difficult for Lance to understand him.

Lancelot laughed once more and then turned and looked out at Gawain’s horse laying dead in the field. He looked back at Lamorak, who nodded slowly, a smile playing at the corners of his lips. Vergil and Brennis were picking over the bodies again.

“And who is this?” Lancelot asked, looking up at Locksley.

“Grummer’s kin.”

“Grummer’s kin? And where’s Grummer?”

“He’s in a spot of trouble from what I can gather,” Lamorak said, sounding serious.

“And The Boys?”

“Both of them injured during our little tilt with the Orkneys.”

“Serious?”

“Come, see for yourself,” Lamorak said, leading Lancelot into the pavilion.

“And who is Grummer traveling with? Is he with Bedivere? Is it Bedivere?”

Lamorak shook his head as he pulled the flap back and waited for Lancelot, Palomides, and Locksley to enter. It was dark. What little light there was came from three tallow candles stuck to a pole. Lancelot stopped, waiting for his eyes to adjust to the darkness. The tight quarters of the pavilion stunk of burned tallow, wet hide, and rotting flesh.

“By the gods, old and new,” Lancelot said, his voice a soft whisper as he put a hand to his mouth. He could see Geoffrey and Godfrey laying on a shared bundle of furs, both of them heavy with fever; their shirts were soaked in sweat, their faces glowing in the dull light of the candles.

“We couldn’t have done even this much if Palomides and his Immortals hadn’t been here to help us,” Lamorak said.

“As Parthians, we pride ourselves on our medical prowess,” Palomides explained. “However limited.”

“Who took off Geoffrey’s leg?” Lancelot asked.

“I did. It was crushed beyond repair. The bone was sticking out. All thanks to Gawain and his brothers.”

“Why did they attack you?”

“Falachd,” Lamorak said, stumbling over the word.

“Am I supposed to understand that? Because I don’t.”

“It’s Gaelic for vengeance…well, it means a little more than just that.”

“And what did you do to earn the wrath of the Orkney Knights?”

“Me? I didn’t do anything. It’s my father they want. I just happened to be more readily available. Well, there’s that, and the fact that I’ve been fucking their mother. I don’t think they like that I’ve bedded her.”

“You what? No, Lam, tell me you’re not fucking her,” Lancelot said, looking up at the man.

“Have you seen their mother?”

“She’s an old and wizened crone,” Lancelot declared.

“You’re talking about the woman I love.”

“Love? You can’t possibly love her. Christ on His Cross, Lam! She’s Arthur’s sister!”

“You think I don’t know that?”

“Why do you say they were looking for Pellinore, when it’s so obvious it’s you they’re after?”

“My father killed Lot, not me. I wasn’t there, remember?”

“All right. All right. We’ll sort it out later. Now, tell me, where’s Grummer? You said he was in trouble. What sort of trouble? Did he not pay his bill at the last whore house the two of you were in?”

“I haven’t seen him.”

Lancelot looked at Locksley.

“ ’Twas the Orkney Knights, aye,” Locksley said.

“Do you speak the same clap-trap Grummer spits out? I can never understand that man when he speaks to me at the best of times.”

“Aye, that I do,” Locksley grinned.

“Why did they attack?” Lancelot asked. “It’s not like Bedivere to get caught with his pants down — ”

“We were nae with Bedivere,” Locksley said.

“Then who were you riding with?”

“Yer kinsman.”

“Mine?”

“Ector deMaris.”

Lancelot turned to look at Lamorak.

“My brother? You’re riding with Ector, and you say nothing?”

“I met up with the lads over-morn, when we were attacked by the Orkneys bros. After that, we had to cut off Geoffrey’s leg, and pull a barb out of Godfrey’s back. With all the confusion, and carnage, it must have slipped my mind.”

“And are you planning to do anything about it?” Lancelot asked.

“Locksley says Geoffrey has an idea, but he’s in no condition to offer up any ideas, is he? Right now, we don’t know if either one of them will make it. We have to take them some place where we know they’ll be looked to.”

“And where would that be?”

“There’s a village with a monastery close by.”

*

The next morning Brennis came riding into the camp at a slow trot, a brace of partridges hanging from his saddle, along with a three-fold brace of large rabbits. His breeches were stained with blood and dirt, his dirty coat torn. The sun crested the trees, casting long shadows that played across the ever-lessening pools of water, shimmering as a cool breeze filtered through the shadows. He untied the game and dropped them to the ground, slipping his bow and quiver over his shoulder before climbing down from the saddle. He picked the carcasses up and walked to the small chopping block outside of Locksley’s pavilion where Vergil sat talking to Baudwin. He rested the bow and quiver of arrows against a small tree.

“We’ve got company coming,” he said.

“What company?” Vergil asked.

“The Queen.”

“What?” Baudwin said, sitting up and looking toward Lancelot where the Knight sat outside his pavilion across the way, talking to Lamorak and Palomides. “Why is she here?”

“She’s looking for Lancelot.”

“That’s Sir Lancelot, to you,” Baudwin said.

“No, that’s Sir to you,” Brennis smiled.

“Perhaps I should teach you some manners?”

“You might try, but I doubt if you will,” Brennis said with a smile. He tossed the two partridges to Vergil.

“Do you?” Baudwin said, his anger getting the better of him. He was quick to get to his feet, his sword and dagger in his hands as he crossed the small campsite in four quick paces.

Brennis watched him, holding one of the rabbit’s in his hand. He waited until the man was close enough, then brought the rabbit up from his side, hitting the Squire in the face with the full force of the rabbit’s weight. As Baudwin stumbled back, taken by complete surprise, Brennis kicked the man in the thigh as hard as he could, pulling his dagger out at the same time. Baudwin tried to step forward, but his leg gave out and he tumbled to the ground as Vergil laughed. Brennis was on top of the man, pinning him, his dagger pressed up under Baudwin’s chin.

“Still want to teach me some manners?” he hissed.

Baudwin said nothing.

“You might want to think that over,” Brennis said, climbing off the man and sheathing his dagger. “And before you think of jumping me while I’ve got my back turned, I can get to the bow before you get to me. That leg isn’t going to hold you up for a while.”

“Brennis?” Locksley asked, stepping out of the pavilion. “What mischief are ye up to, lad?”

“The Queen is following,” he said.

“I heard. An’ Pellinore?”

“I suppose.”

“Which Queen is it?” Locksley asked.

“Which? How many are there?” Brennis said, confused.

“Two. Isould an’ Tristan are ridin’ with ‘em.”

“I did not know that.”

“That’s why yer the Squire,” Locksley smiled, pulling his sword out of his scabbard and looking at the blade. He ran a thumb along the edge and nodded to himself before crossing the campsite where Lancelot and Lamorak were talking to Palomides. He drove the sword into the ground and turned to look at Brennis. “If ye can find the time, lad. I’ve some nicks on the edge.”

“Is that part of my duties?” Brennis asked, looking up from the rabbit he was skinning.

“Yer duties be whate’er I tell ye,” Locksley added as he crossed the camp.

“Do you want to clean one of the rabbits?” Brennis said to Baudwin. “It’ll be faster.”

*

“Brennis says yer Da’s on the trail,” Locksley said, sitting beside the small fire between Palomides and Lamorak. Mustafa, the Immortal, was cooking, the scent of the food intoxicating. Locksley turned to look at what the man was cooking.

“What is that?” he asked, looking at Palomides. “Is there nae this man canna do?”

“Kusksi,” Palomides said with a broad smile.

“I should send him o’er t’ teach Brennis ‘ow to cook.”

“My Da?” Lamorak asked at the same time, and Locksley turned to look at him.

“Aye.” He looked at Palomides again. “And what is Kusksi?”

“Rolled up balls of flour and water. It’s quite flavourful because you can eat it with anything.”

“How does the boy know it’s my Da’?” Lamorak asked.

“We come on ‘em camped two days over-morn,” Locksley smiled, watching Mustafa stir the mixture with a large wooden spoon. “ ‘E was with the Queen,” he added.

“The Queen?” Lancelot said, looking up.

“Aye. Did I nae tell ye the Queen was scourin’ about fer ye?”

“No. You forgot that little detail as well,” Lancelot said.

“It’s been a fright ‘ere, these past two days,” Locksley said, looking at the man.

“And why is Pellinore with her?” Palomides asked.

“I didna say ‘e was. ‘E’s makin’ ‘is way South, is all — or was. T’ Camelot, same as ever’one else.”

“What do you mean, was?” Lamorak asked.

“ ‘E’s been took ill.”

“Ill? How? And why did you not say anything before?”

“As I said tofore, things have been ‘ectic.”

“Who is he traveling with?” Lamorak asked.

“Yer Da? I wanna say yer sister? An’ yer kinswoman? Aye. A fine lookin’ woman, she was,” he added.

Lamorak sat back and nodded slowly. “That would be Gwenellyn. They were ridin’ with Mark’s Queen last I heard; her, and her Knight.”

“Mark’s Queen?” Palomides asked.

“I wot not who she is,” Locksley said with a shrug. “She was nae there when we arrived.”

“And the Knight?” Palomides asked. “Did you see the Knight?”

“Nae. I dinna can say I saw ’im. But if ‘e’s from Mark’s court?”

“It has to be Tristan ,” Palomides said.

“D’ye think it so?” Locksley asked.

Palomides nodded as Mustafa said something, and the three Knights looked at Palomides. He smiled and turned to look at them.

“He says if it’s Tristan , maybe he’ll stand and fight this time.”

“You’d better hope for your sake that he doesn’t,” Lamorak said.

“Ye canna be goin’ on about ‘im. We have t’ secure Grummer an’ Ector afore we do anythin’ else,” Locksley said.

“Yes,” Lancelot said.

“And how do you propose to do that?” Lamorak asked.

“Well, I had been thinkin’ of enterin’ the castle Keep an’ freein’ ‘em.”

“Just like that? Do you think Turquine’s going to open the door when you knock? Is that your plan?”

“Well, with the Queen on ‘er way, I was thinkin’ I might convince ‘er t’ send some of ‘er Knights out to do battle beside me,” Locksley said.

“You expect the Queen to send out her Honour Guard and help you free the prisoners?” Lancelot smiled, shaking his head.

“Why do ye have t’ say it like that?” Locksley asked.

“Say it like what?” Lancelot replied.

“I rather hoped yerself’d stand endlong at my side,” Locksley said.

“Me?”

“Is Ector nae yer kin? Yer blood kin?” Locksley reminded him.

“That he is,” Lancelot smiled.

“Is that nae good enow? Or do I have t’ pay ye fer yer mastery?”

“Pay me? You don’t have enough gold to pay me for my services, lad,” Lancelot laughed.

“I will. As soon as the Queen’s behest —”

“Her what? For God’s sake, man! Do you expect me to understand that clap-trap you use? Speak so a man can understand what you’re saying,” Lancelot said.

“She’s offered right proper coinage to whiche’er of ‘er Knights finds ye,” Locksley pointed out.

“At her behest, you said? She’s offered a reward for my safe return? Is that what you mean?”

“Aye. An’ I plan t’ claim it,” Locksley smiled.

Palomides laughed, slapping his thigh. “Capitol!”

“Capitol?” Lamorak asked. “He’s not one of the Queen’s Guards. He cannot claim her behest, no matter what he thinks.” He turned to look at Locksley. “Listen, boy, that’s not how it works. The Queen only offers her so-called behest to her own Guards. All those Knights with her are members of the Queen’s Guard. The King has his Guards, and the Queen has hers. The King’s Guards travel with him wherever he goes. Just as the Queen’s Guards go with her. Any reward — behest as you say — she might offer, is only offered to them. Not you, not even Lance, or Palomides here.”

“Is this true?” Locksley asked, looking at Lancelot, who nodded.

“I’m sorry, but that’s just the way it is. I’m sure Grummer would have told you the way things work —”

“Certes, he would,” Locksley said. “ ’Twas his disadventure t’ be ensnared,” he said, standing up.

“Where are you going?” Lamorak asked.

“I shall hie out, anon—”

“You can’t leave!” Lamorak said. “The Queen is coming.”

“Aye, an’ Turquine’s Keep is a day’s ride —”

“You can’t go out alone,” Lamorak said.

“I have Brennis. ‘e may be just a lad, but he has pluck.”

“Pluck?” Lancelot smiled, looking at the boy as he tossed a piece of rabbit to Baudwin.

“I shall ride with him,” Palomides said. He called out to the Amal the Immortal as Locksley looked across the camp where Brennis sat in front of the fire, placing another rabbit on the spit.

“Brennis! Break camp! We ride!”

Such detailed gore and violence, Ben. It is like you are actually there reporting from the battlefields. You hold nothing back. I admit to you that I skim over some of it, just too gruesome for me. I puzzled over this awkward sentence: "Grummer was never one to not take advantage of a situation." But that actually sums him up perfectly. Your illustrations remind me of adventure books I read as a child. Perfect.