THE LADY, CAPTIVE

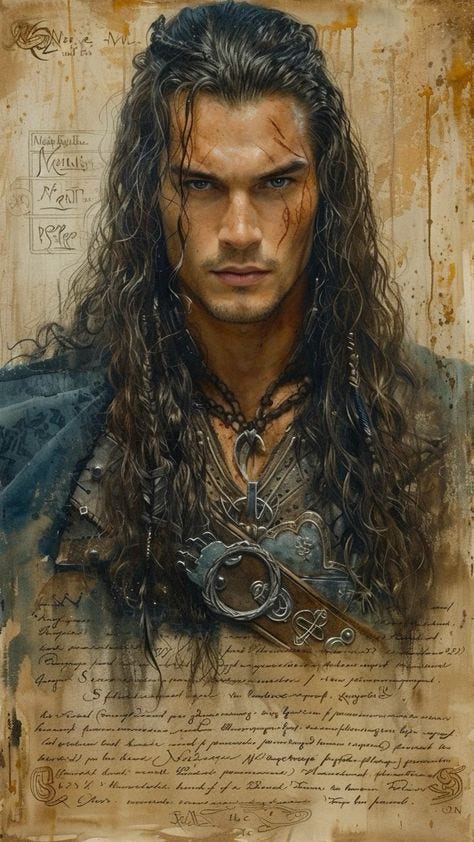

Locksley stood beside Palomides on a low sloping hill, looking out over the Keep rising up in the distance. They were standing inside a small copse of trees, a slow, lazy wind sloughing through the branches; the pungent smell of the dead leaves they’d kicked up, surrounding them. They stood at a distance, but even so they could make out the wide moat surrounding the Keep. The drawbridge was down — there were carts of produce and materials passing in and out — and Locksley supposed that was because there were no perceived threats in the area. The drawbridge would be raised soon enough the moment Lamorak and Lancelot appeared on the field to issue their challenge. That was the moment, he decided, when he’d have to slip into the moat and make his way into the sewage pipe.

“And you are certain this is the best way in, effendi?” Palomides asked, shaking his head.

“Aye.,” Locksley replied, looking at the man with a quizzical knot of his brow. “Geoffrey said ’twas the least beheld of any Hold, or Keep.”

As they watched, the garbage chute above the sewage pipe opened up.

“Och, what’s that?” Locksley asked, watching as a barrow full of debris slid into the moat. He looked at Palomides, and the man grinned.

“Refuse, effendi?” Palomides offered with a laugh.

“Aye,” Locksley said with a slow nod. “The chute t’is then,” he added, making up his mind.

“Are you certain, effendi?”

“I’ve Nae desire t’ go in through that cess pool of shit,” Locksley declared.

“The chute it is then,” Palomides said, and laughed again.

Locksley nodded. “An’ what’s that name ye keep sayin’ on me?”

“Effendi?”

“Aye, that one,” Locksley nodded.

“It means: ‘respected friend’,” Palomides explained. “A term of endearment.”

“Nae just friend, but respected friend?”

“Aye,” Palomides smiled. “Effendi.”

“I’m pleased ye think so high on me,” Locksley said at last.

“When will you attack?” Palomides asked.

“ ‘Twould be best under the cloak of night, think ye nae?” Locksley said. “But I’m sorely aggrieved t’ think Lam an’ Lance will Nae wait that long.”

“And if they attack too soon? What then? They are but two against a multitude.”

“A multitude? An’ how many is that? A multitude?”

“Two score,” Palomides said without hesitation, and Locksley fixed a stare at him.

“Two score? Ye seem assured on that?”

“Any more than that, and there is no room to wield your weapon,” the man said.

“And ye’ve fought against a multitude?”

“Have you never been in a mêlée? Or in a battle?”

“Aye, I’ve been t’ battle,” Locksley said with a slow nod.

“Ah, yes, so you have. Knight of the Field, was it not?” Palomides smiled.

Locksley looked at Palomides and nodded, not knowing how much the man knew of the story. It’s possible he knows more than he should, Locksley thought, but then, he was his Uncle’s friend and that had to stand for something, he thought. Grummer being Grummer, Locksley had every reason to believe his uncle may have said too much while lost in his cups.

“By the hand of Pellinore, no less?” Palomides said, and Locksley wondered if that was a note of awe he’d heard in the man’s voice

“Nae less,” Locksley nodded.

“And how is it that a young bachelor Knight finds himself at a king’s side?” Palomides asked a moment later. Locksley told himself it wasn’t awe he’d heard the moment before.

“I killed my way there,” he said, staring at the man.

“And what of Lot’s King’s Guards? Every king has his guards.”

“Overthrown,” Locksley said, and remembered driving the point of his sword through a man’s face — one of Lot’s six King’s Guards. Locksley had pushed with all his weight against the man, until the blade came out through the back of the man’s helm. Without hesitating, Locksley pushed the King’s Guard back, with his shoulder, and turned, ducking as Lot’s war hammer sliced the air above him, taking the dead man’s head off. Locksley had struck without a second thought.

Definitely a multitude.

“By your hand, effendi?” Palomides asked softly, and Locksley remembered the dead knights around him.

“Pellinore’s,” Locksley lied.

“And Lot?”

“Dead — by Pellinore’s hand,” he was quick to add, turning back into the trees and walking to where they’d left his horse and the camel tied up.

“And so I heard,” Palomides smiled, following.

“Ye’ve heard overmuch, it seems,”

“And what do you mean by that, effendi?” Palomides was still smiling.

Locksley stopped and looked at the man.

“Ye were nae there. Ye saw nae, an’ yet, ye know I was made Knight o’ the Field by the hand of the king?”

“I do. But all of Camelot knows the tale.”

“My Uncle has spoken to ye on it?”

“He has.”

“Mayhap he’s said overmuch?”

“Mayhap,” Palomides grinned. “But, effendi, it was Pellinore who spoke of you at Camelot Court.

Locksley nodded, turned, and reached for the horse’s lead tied to a tree. He walked the horse out of the woods and into a clearing where he climbed up into the saddle. He waited as Palomides climbed on the huge camel and urged the beast up to its full height. Locksley’s horse back pedalled as the beast rose up; Locksley patted the horse gently.

“An’ what is it me Uncle said, an ye will?” Locksley asked a moment later.

“The truth.”

“The truth? An’ what say ye t’ that, then?” he added.

“That Pellinore will hold you in high regard should you come across his niece, effendi.”

“I’m adoubted Pellinore will say ought,” Locksley said, pulling on the reins and turning the horse.

“Lam then?” Palomides said with a smile.

“That, effendi, is a bridge t’ be crossed,” Locksley laughed. “T’is his sister’s opinion t’ heed as well.”

They rode across the open countryside. The dew-laden grass rippled in the wind, the distant trees bent and weathered, were swaying gently; clouds were scurrying across a cobalt sky. Locksley looked at the Keep looming over the low valley, looking like a bright spectre in the distance. He knew whoever was standing on the parapets would see them, but he told himself it didn’t matter. They’d be questioning their own eyes at the sight of Palomides and his camel lumbering across the valley.

They reached the edge of a large wood where they’d set up camp the night before. There was a natural clearing with a small stream; a fire, warm and inviting, glowed red. Brennis had returned late in the afternoon, and being the good Squire he was, had helped set up the camp and prepare the meal. His first concern had been for both Geoffrey and Godfrey, and Locksley was glad to see that. Mustafa and Amal watched over the Boys, but Brennis had brought game, as well as tubers and wild greens, which he dropped into a pot and let to stew. Mustafa added ingredients so that there was more than enough for all of them. Locksley watched as Brennis soaked a loaf of bread and fed it to Godfrey.

He knew he had to get them to an apothecary, or even a nunnery — preferably a whore house, he thought, where they could all rest for a few days and perhaps enjoy a sport or two. But how much time could they wait, he wondered? The tournament in Camelot was two weeks away. He was certain they could make it in as little as four days of hard riding, but what about Ector and Grummer? Being held captive for two weeks, there was no way of knowing if they were in any shape to ride.

As the sun slowly settled and the sky gave way to a brilliant red over the distant horizon, Lamorak and Lancelot approached; Vergil and Baudwin trailing behind, leading two horses laden with supplies.

“Have you no men-at-arms to accompany you?” Palomides asked Lancelot as they sat around a crackling fire, eating the last of the stew.

“I did. Lionel, my nephew — Ector’s nephew as well, and closer kin to him in all truth, we being but half brothers.”

“Ector is yer ‘alf-brother?” Locksley asked. “An’ yet, ‘e dubs ye as his full-blooded kin?”

“Does he?”

“So ‘e said t’ me, afore ‘e was captive-made by Turquine.”

“He was always sentimental. I’m four years older than him. Maybe five? But older. I never paid him a day’s notice when I was in Benwick. He was a page, at best. He brought me wine on occasion.”

“And now he’s a Knight,” Lamorak laughed.

“Yes. My father’s bastard child; a Knight because of my father’s shame —”

“Aye, an’ is that yer matter?” Locksley smiled.

“My father’s shame, is my shame. That’s how these things work.”

“And know ye that ‘e’s held captive in yon Keep?” Locksley asked.

“And do you know the Queen and her Guards now follow?” Lamorack asked.

“How so?”

“I sent a rider out when we were at my father’s camp. I told her I had Lancelot but first we needed to address the issue of his captive brother.”

“And she replied?”

“Why would we stay for an answer?” he laughed. “Let my sister deal with that. She wants to be regent, let her.”

“And when do you face Turquine?” Palomides asked.

“On the morrow,” Lancelot said, and Lamorak smiled.

Locksley looked at Brennis who was waiting with his bow drawn taut in his hands. Maybe it would be easier going in through the sewer pipe? he told himself. But scaling the wall and using the chute made more sense. What if there was a locked gate at the other end of the pipe? What if the moat’s deep, and I have to swim? I’d never make it, not with all this maille I’m wearing. Taking it off and going in through the pipe unprotected made no sense, but it was something he’d have to do all the same. If he scaled the wall, he might still be able to wear the chain. All he had to do was get up the wall, open the chute and climb through. The chute looked large enough. He wondered if he’d be able to pull himself up with the added weight.

“Are you ready?” Brennis asked.

“Has Turquine dropped the bridge?”

“Not that I can see.”

“We’ll ‘ave t’ wait. We need a distraction.”

“Did Lancelot say when he was coming out?”

“‘E said ‘e’d give me time t’ get close.”

“And how will he know that we’re close?” Brennis asked.

“I dinna can. Maybe Vergil’s on a hill, watchin’? Or Baudwin?”

Brennis laughed. “If he can see us, we’re not very well hidden.”

“There!” Locksley said, watching both Lancelot and Lamorak ride out of the woods. Vergil followed, leading a pack horse loaded with weapons; Baudwin following behind. There were a dozen spears of varying lengths, from the Roman pilium, to Saxon lances made more deadly when delivered on horseback. There were four shields, two each belonging to both Knights. Locksley could see the long-handled axe Lamorak preferred using, hanging from his saddle, along with his broadsword, which gave him more mobility than having it hang at his side.

“Do you think he’ll accept the challenge?” Brennis asked.

“‘E won’t have a choice,” Locksley replied. “A Knight challenges ye in front o’ the men ye ‘spect t’ follow ye, what think ye? ‘e doesna have a choice, does ‘e? An’ that’s when we move,” he said, hearing the pulleys used to lower the drawbridge come to life.

He could see the top of the walls lined with Turquine’s mercenaries. Were they Knights Turquine had captured and turned to his cause, or had he somehow sent word out? They were an odd assortment of men from what he could see. Some were obviously Saxon, while others were Norsemen, and still others, from tribes to the East — from foreign lands with exotic names like Samarkand and Constantinople.

Locksley kept them in sight as he and Brennis skirted along the tree line after hearing the drawbridge fall. A moment later, there was a cheer from the walls and Locksley pointed at a small shrub. Brennis grinned and they made their way toward the bush, the moat yawning in front of them.

“I trust it’s Nae too deep,” Locksley said, slipping down the steep embankment, the water cold as it seeped through his maille. The water rose up to his chin, and Locksley found himself standing on his tip-toes, gasping for breath.

Brennis scrambled up the other side of the moat and brought out the arrow Vergil helped him devise the night before. It was triple-barbed, the last barb meant to spread out when someone tried to pull it out. He stood with his back against the wall, aimed at the chute, and watched as the arrow lodged deep into the door. There was a string attached to the arrow, the end of it tied to a length of rope.

Locksley climbed out of the moat and watched as Brennis pulled on the string; he saw the rope rise up into the air. He looked up at the wall in case someone should look over — knowing it would be the end for both of them — and finally stood beside Brennis with his back against the wall. Locksley looked up at the arrow, the rope dangling from the end.

“What am I s’posed t’ do with that?” he asked, and Brennis smiled.

“Watch,” the Squire grinned. He flipped the rope and it wrapped around the arrow; he flipped it again, and a third time, and then pulled on the line.

“An’ ye ‘spect that’ll do the trick?”

“I simply pull on the line to get the chute open.”

“An’ then what?”

Brennis reached down for the small bag hanging from his belt. In it was a hook. He pulled on the line and the arrow bent, pulling the door open.

“Willow,” he said. “It bends and doesn’t break—as long as it’s fresh. We tie this end of the rope to the hook, throw it up and catch the open door, then climb in.”

“We?”

“Did you think I was going to let you go in there alone? I’m not weighed down with maille. I can climb without fear of the hook breaking free. I can also secure the rope inside and lower it to you.”

“Ye’ve no need t’ do it,” Locksley said.

“Yes I do,” Brennis said. “It’s Sir Grummer in there. I’ve known the man since I was a child. He never knew my name, always got it wrong, forgot who my mother was, but was always there to see that I got what I needed. I owe it to the man to try.”

“Then ‘elp me get this maille off,” Locksley said.

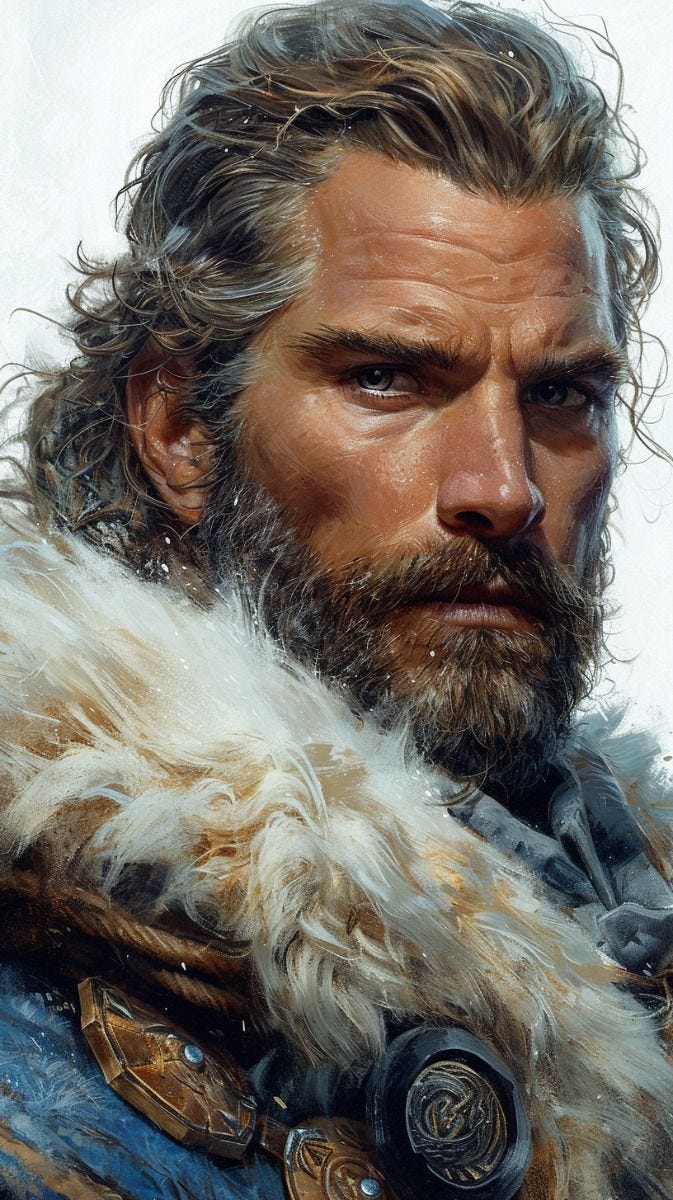

Lamorak watched the drawbridge fall, felt a surge of cold air rushing at him, the dust and grime stinging his eyes. He looked at Lancelot and grinned, pulling the strap of his war axe over his gloved hand. He reached out for a spear, and Vergil brought him one of the shorter lances. Eight feet long, it offered the rider more flexibility. A man could rush into a mêlée and put five riders down before they could react; a rider with a barbed tip would kill every man he confronted.

“We’re decided then, are we?” Lamorak asked.

“Yes. I’ll take Turquine, and you get all the fun,” Lancelot said drily. “If he comes out with an escort, that is, which I expect he will.”

“Well, yes, there is that. But when has Turquine ever disappointed you when it comes to doing something you expect? Maybe you should ask yourself, when’s the last time he did the right thing? He’s not going to come out here alone, and we both know it.”

“Again, you get to have all the fun,” Lancelot said.

“How many, do you think?”

“No less than a score.”

Lamorak looked up at the walls of the Keep and saw the mercenaries lined up against the parapets. He estimated there had to be at least thirty, or forty men, and hoped Locksley was as good as both Pellinore, and Grummer, said he was. He wasn’t going to worry about it; he’d have his hands full soon enough.

“I think we’re about to find out,” Lancelot said. He dropped his visor and held out his hand for the long Saxon spear. He looked down at Baudwin. “How many do we have?”

“Three.”

“Give me the tight shield,” he said, watching as Turquine’s horse thundered across the drawbridge. He was followed by his riders.

“I count one score and ten!” Lamorak laughed. “At least they made it a fair fight.”

“Are you sure, Lam?” Vergil asked, handing the small shield to Baudwin who brought it over to Lancelot. Grabbing his bow and a quiver full of arrows, Vergil mounted his horse and waited.

“I won’t say no to you watching my back,” Lamorak said. “But don’t shoot everything you see.”

“Why would you say that?” Vergil said with a laugh.

“When you’re a Knight riding into battle, you’ll be grateful for two things. A Squire to watch you back, and one who knows when to stand down.”

“You take all the fun out of it,” Vergil said.

“My very words,” Lancelot laughed.

“Shall we then?” Lamorak spurred his horse ahead and Lancelot followed.

Lamorak went to the right, away from Tarquine, while Lancelot rode directly at him. There was a moment of confusion — it became obvious that Turquine had his own idea as to whom he should face — and Lancelot crashed into the riders with his long spear, shattering it on impact. He dropped the shaft and picked up his mace, the three foot chain and balled spike a deadly weapon in his hands.

Lamorak approached the riders with his short spear, catching them unprepared. The first three Knights were unable to get their shields up high enough as Lamorak lifted the tip of his spear, catching the first rider in the throat; dropping the tip of the spear down just as quick, he caught the second Knight in the ribs were he knew the maille would be weakest; swinging the weapon against the third Knight and catching the Knight’s shield, the pointed barb pierced the shield and impaled the man. Lamorak dropped the spear and slid his war axe down his wrist, letting go a tremendous backhanded swing that caught the man on his right, only to bring the weapon back with a forehand slam that took the man on his left in the neck. The blood sprayed and Lamorak laughed.

Lamorak heard an arrow as it passed by his head, and saw the man behind him drop his sword, the weapon falling out of his hands as an arrow passed through his throat. He looked to the left and saw Vergil smile as he notched another arrow and let it fly, catching a Knight under the armpit. Lamorak turned and saw another Knight fall where a moment before Lancelot was swinging his mace. Baudwin grinned at Vergil and the two Squires separated, each following the battling Knights.

Lamorak watched Lancelot riding toward Baudwin. Baudwin was quick to jump off his horse, drop his bow, and fetch the second of the long Saxon lances; he held it up and Lancelot reached out with his hand and snatched it from him. Out of the corner of his eye, Lamorak saw Turquine behind a circle of six Knights. He spurred his horse and rode at Turquine’s knights; he heard an arrow flying past him and watched as the man to the left of him fell. It was only a heartbeat later that a second Knight’s horse buckled, and fell, as Lamorak crashed into the other Knights, his battle axe catching flesh and taking root.

Turquine spurred his horse and Lamorak saw Lancelot come in behind him at blinding speed. The Knight never let up, and drove his spear into Turquine’s shield. The lance shattered, a large splinter of wood spearing Turquine underneath the helm, like a child torturing a bug. Both horses reared up, screaming; Turquine’s horse skewered with a thin sliver of lance that pierced its neck. Lancelot had his mace in hand, the spiked ball driving full force into Turquine’s face and watched as the man fell to the ground, dead.

Locksley reached up, stretching out and grabbing the hand Brennis offered him, surprised at how easily the lad was able to pull him up into the narrow chute. He looked down at the Keep’s wall sloping below him — the garbage a slick stain on the wall — as he felt his hand slipping, and reached up with his other hand. He scrambled in, feet flailing as he slid down the slick chute, crashing into the door. His foot kicked the hook as he slid, dislodging it and sending it to the mound of garbage below. Brennis tried reaching out for the hook, but he was too late. He crawled forward, looking over the edge of the chute at the garbage piled below, where the hook lay on top.

“That pretty well settles it for us,” Brennis said with a laugh, leaning back against the wall and looking at Locksley. “It’s all up to you now.”

“Me?”

“Who else is there? Do you see another Knight here? I’m just a Squire — newly made, let me add — and I have no experience with rescuing knights, let alone princesses. You’ll have to rescue the Princess, free the captive knights, and probably fight all the soldiers we saw lining the wall above.”

“An’ what’ll yerself be doin’ in the meantime?” Locksley asked. “While I’m doin’ all this rescuin’ an’ gaddin’ about?”

“Someone has to think of a way to get us out of here.”

“Ahh,” Locksley smiled, nodding. “An’ those’re nae soldiers, just so ye know; they’re miscreants an’ mercenaries. They’ll be quick t’ leave as soon as the pilling’s run out.”

“The pilling?”

“Aye. The coinage; their fee?” Locksley explained.

“And do you know when’s that going to be? Do you think it will be today?”

“Well, if Lancelot an’ Lam o’ercome Turquine an’ his Knights, it canna be long after that.”

“Are you saying we should just wait?”

“Nae, lad,” Locksley said with a wide grin. “That’d make this a fool’s errand. D’ye count yerself a fool? Nae? Have ye got yer bow?”

“I’m never without it,” Brennis said, reaching behind him.

“Then let’s us go an’ find us a Princess,” Locksley smiled.

“Aye, let’s,” Brennis laughed, and kicking the door, slid out of the chute.

Locksley lost his footing as soon as Brennis jumped down — the chute suddenly tipped and the door opened again. He slid down its length, coming dangerously close to the opening. He managed to grab a length of timber and scramble back up, finding small perches along the sides of the walls until the chute tipped back again. He kicked the door open and fell to the floor with a heavy thump, looking up at Brennis who grinned and reached out a hand to help him up.

“This whole thing is made up of timbered cedar,” Brennis said.

“Ye’d be astonied were ye t’ know most such places’re purfled—”

“Purfled?” Brennis asked, pausing to look at Locksley. “Is that even a word?”

“Ye wot not what purfled is?”

“I don’t,” Brennis said.

“Ach, lad, I canna teach ye now,” Locksley said, a note of impatience in his voice.

“I understand you speak a different tongue up beyond the wall,” Brennis said, “but I don’t live there. I’ve never been this far from The Red Lion before. I was born in a whorehouse, remember? I can understand most of what you say because the Knights that attended to the pleasures of the house came from different places—but I don’t understand all of what you say; not all the time. I usually just nod my head and hope I understood you properly. But if you’re going to be living in Camelot, it’s you that has to change, not me.”

Locksley considered what Brennis said, and nodded.

“Purfle is what the lassies do when they’re sittin’ at the fireside, stitchin’ with their needles, makin’ pretty pictures —”

“Embroidery?”

“Is that what ye say then?”

“Some of the whores were at it when they had the time,” Brennis said.

“Well, if ’tis, it’s what we up beyond the wall call what Lords do t’ their castles an’ Keeps, sealin’ the walls with muck an’ paintin’ ‘em to look like stone.”

“Purfle?”

“Aye.”

“It’s a damnable tongue from what I can tell,” Brennis laughed.

“Aye, ’tis that I’ve nae doubt.”

They made their way down a narrow hallway, coming to a set of wooden stairs made of half cut timbers. Locksley looked up at where the stairs seemed to end at the floor above them. He looked down, looked at Brennis, and then nodded to himself, following the rough-hewn stairs down into the depths of the Keep; Brennis followed. There was little light, what light there was coming through cracks in the walls where the mortar outside had crumbled. Shadowed timbers stretched across the stairs until they came to the main floor where they could see the doors of the Keep thrown open, daylight spilling across the rough floor.

They both crouched down and could see the Mercenaries beyond the Keep’s doors, some of them hurrying through the Courtyard and up carved steps leading to the parapets above. The Courtyard was littered with dead Saxons, and it looked to Locksley as if they may have been caught unaware. Most of the Mercenaries were sorting through the pockets and purses of the dead, cutting off fingers for the rings they wore. The drawbridge was down, the gates wide open, and Locksley could see horses, wide-eyed and frantic — some frothing at their bits, some basted in blood — fighting with groomsmen. Locksley crept down the stairs, keeping close to the wall and using the shadows he found, making his way down to the lower floor.

When they came to the landing they found the door open, and Locksley peered around the corner. There were several torches newly lighted, and several doors that he could see, some open. He heard voices in the distance. A woman was talking, her voice sounding loud and insistent.

“I dinna care what ‘e said. Do ye understan’ me?”

“But, my Lady Queen —”

“Dwarf! Enough! Accolon was a fool, an’ ‘is Saxons’re dead ‘cause of it — by Turquine’s order, as nae doubt ye saw. Do ye ken what that means? There’s nae man ‘ere t’ defend this hovel. That’s Lancelot an’ Lamorak out there. Have ye nae seen what they’ve done? Two score men rode out t’ face ‘em. Nae! Two score an’ ten! Two men — against a multitude! Slain, they are! Defeated. Would ye think I wanna stay?”

“But you cannot escape, my Lady!” the man exclaimed. “There’s no way but for the gate.”

“Of course I can. D’ye think I’m gonna stay ‘ere an’ let m’self be tossed atwixt Lancelot an’ de Gales? I’m nae man’s prized cunny. D’ya think Turquine spent ‘is time buildin’ this shit-hole without thinkin’ of a way out? There’re more’n just the dungeon down ‘ere,” she said, her voice trailing off as she made her way down the steps.

Locksley drew his sword, understanding why Lamorak preferred his war axe, and Lancelot his war mace. There was little room for him to swing his weapon in the close confines of the stairs. He looked at Brennis, an arrow notched in his bow, ready for anything.

He could hear a voice in the darkness calling out, and shortly after that, the incessant banging of something against a door. He stopped, trying to determine where the sound was coming from. Brennis stopped to listen, and pointed down a narrow passage. There were more voices calling out in the distance.

“I think we found them,” Brennis grinned.

“Go ye that way, an’ I’ll this. Kill anyone what gets in yer way.”

Brennis nodded, and was soon lost to the darkness.

Locksley kept close to the wall. The stench of wet, dank mud, closed in about him as he came to a barred door. It was shut tight and he pressed his ear against it, listening. He heard nothing, rapped his knuckles on it gently, and waited. When he decided there was no one in the room, he made his way down the passage, looking into three other rooms he came across.

“Is someone there?” a voice called out. “Hello? Is there someone out there? I’m in here! Help me, please.”

“My Lady?” Locksley said, keeping his voice low.

“Who is it? Who’s there?” she called out from the other side of the door.

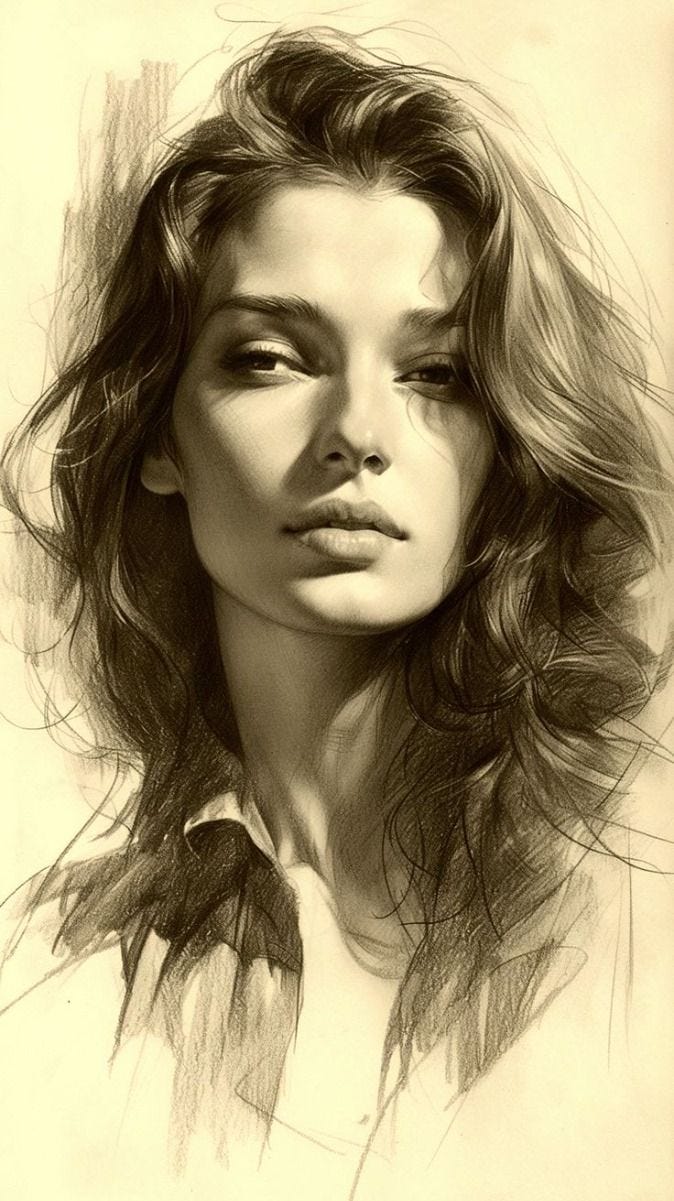

“Quiet!” Locksley said, approaching the door. There was a timber barring the door, and Locksley lifted it up and set it to the side, against the wall. He could hear voices in the passageway — saw the flickering light of a torch rounding the corner — and pushed the door open. He saw her dishevelled figure standing in the shadows. What light there was came from the torches in the hallway and dimmed as soon as he closed the door behind him. Waiting at the door, he was listening to the voices as they grew louder.

“Who are you?” she asked.

“Sir Locksley, of Inverness Beyond-the-Wall,” he replied, a hand to his lips hoping to silence her.

“Inverness? Sir Grummer’s knave?” she asked, sounding cautious.

“Aye. Lady Gwenellyn?” he said, in a hoarse whisper. “I’ve come to rescue ye.”

“Have ye?” a woman’s voice outside the door said with a gentle laugh. “Such a gallant young man,” she added, pulling the door tight and fitting the wooden plank into place.

“My Lady! What are you doing?” Gwenellyn called out, running to the door and throwing her weight against it. She pounded on the door in frustration. “You cannot leave us here!”

“I canna be takin’ ye t’ Camelot with me now then, can I? I canna let anyone know I was here. Ye’ve gone from bein’ an asset, my child, t’ bein’ a liability. I’m sorry, but it’s for the best.”

“No! You cannot leave us here!”

“Oh, but I can. Bring me that torch, dwarf,” Locksley heard her say.

“What are you doing!” he called out.

“Turquine’s dead; Accolon, an’ ‘is Saxons’re dead — more the fool he for havin’ trusted Turquine, I say — ‘alf the Knights what rode with Turquine this very morn, lay assorted on the field. Dead. There are nae tales for the dead as the ol’ saw says, an’ well it should. I’m sorry child, but it’s for the best,” she said, tossing the torch into the empty cell next to them. The torch gutted for a moment, and then the straw on the floor caught and the flames leapt up with a thirsting hunger, carrying the fire up to the wooden walls, where the timbers caught and burst into flame.

Holy Moley. Where's that canny lad Brennis, then? He better get his arse back there and make it quick! I loved this line: “An’ what’ll yerself be doin’ in the meantime?” Locksley asked. “While I’m doin’ all this rescuin’ an’ gaddin’ about?” This whole thing reads like a screen play if you ask me.