CHAPTER IV

1941

Dad took up water painting. I think it served as some kind of a release for him, from the inner turmoil he seemed to suffer from with having gone through the Great War. Inner turmoil was what Winnie called it. They were just memories, plain and simple, and they haunted his dreams as much as they haunted his waking hours. It seemed that with Jack caught up in the Blitz over there in London, Dad was suffering through the war again, one day at a time.

“It’s like he’s fighting his own damned war,” Mom said with a note of worry in her voice. She watched Dad sleeping in his chair with the newspaper spread open on his lap. His left leg was resting on a small stool, and he was clenching and unclenching his jaw. We could hear him grinding his teeth.

We’d sit near the radio every evening listening to the war report coming in over the CBC. Dad calmly smoked his cigar while making notes on legal pads he kept near his chair. Mom sat in her own chair knitting sweaters she intended to ship off to Europe for the war effort—but I don’t think she ever did. Jenny sat on the ottoman beside Mom, watching as she learned to knit; she only managed a row or two before being sent off to bed. Freddy sat at Mon’s feet holding the yarn for her as he struggled to read the newspaper spread out on the floor in front of him.

I was too anxious to sit. I paced the floor with the impatience of a caged animal, watching Dad write page after page of endless notes. Soon the notes Dad wrote turned into scribbles, the scribbles became doodles, and the doodles drawings. I watched Winnie reading her anatomy books in the kitchen under the pale light hanging above her, and couldn’t understand how she didn’t want to hear the news.

Dad bought large maps of Europe—France, Germany, and Holland; Italy, England and Austria—and we watched him tacking them up on the walls of Jack’s old room. I wondered why Dad wouldn’t allow me to move into the room now that Jack was gone. I was still sharing a room with Freddy—like I had been since he was three.

Mom came walking out of the kitchen wiping her hands on a dishtowel the day Dad tried dragging the radio into Jack’s room as well. She calmly asked him what he thought he was doing.

“I’m making a war room,” Dad said proudly.

“A what?”

“I plan to know where Jack is as much as I can. See?” He pointed to a spot on the French coast.

“What’s that?” Mom asked.

“Dunkirk. That’s where he said he was headed for, the last time he wrote. Dunkirk.” And he drew a circle around the name.

“He never said anything of the sort,” Mom insisted.

“Of course he didn’t say it in so many words,” Dad laughed. “But it’s what he meant. It’s the only thing that makes any sense. It’s the gateway to Europe. The war should be over within the year once they get a foothold there,” he added, knocking on the map as if he were making a point.

“And what if I want to hear a program in the afternoon?”

“A program?” He seemed taken aback by the change of subject.

“What am I supposed to do? Drag the damned thing out again?”

“What program?” Dad asked.

“What do you think I do all day when you’re gone? Do you think I wait here in dead silence waiting for you to come home?”

“Do? What do you mean?” He seemed flustered, as if he’d never thought of Mom as doing anything. “You clean the house, I suppose. And take care of things for me.”

Mom looked at him and blinked. It was as if someone slapped her in the face with a cold rag or something—and then she smiled. I wouldn’t say it was a warm, inviting smile, but the kind of smile that should have made him sit up and take notice. He didn’t.

“Do you expect me to give up listening to my music?” she asked.

“You can hear it from here,” Dad said, patting the radio gently. “It’s loud enough.”

“This is becoming an obsession,” she said throwing the dishtowel. “Don’t you see what it’s doing?”

“Doing? What do you mean: ‘What it’s doing’? It’s not doing anything! Obsessed? What’s there to be obsessed about?”

“Don’t you see what you’re doing?”

“No. I don’t. Why don’t you tell me?”

“It’s eating at you. You grind your teeth at night; you cry in your sleep—you kick your feet when you’re in bed, like you’re running. It’s happening all over again, the way it was in Toronto.”

“My God! You think I’m trying to fight the war through Jack! Is that it?”

“Something like that,” Mom said, standing firm and not relenting, even as the silence grew between them.

“Jesus Christ woman! That’s the last thing I want!”

“Then show me that you’re not. I mean...maps? Battlefields? Is that supposed to be the new Western Front?” she added, drawing a circle on one of the maps with her finger. “What am I supposed to think? What do you think it looks like? I can’t let you bring the radio into this room. I won’t let you bring it. Are you listening, Daniel? It belongs out there. In the front room for the whole family to listen to! I won’t allow your obsession to take over this family.”

“Obsession? Why are you calling it an obsession?”

“What do you want me to call it? If you want to take over Jack’s room and follow the war with your drawings and scribbling, fine. But I won’t let you move the house around to satisfy your needs—”

“Can’t, or won’t?”

“What difference does it make?” she said quickly, her resolve a determined steadfastness. “The radio stays in the front room; where it belongs. This is my house as much as you think it’s yours. I do more than just look after it for you; I do more than just clean it for you. I won’t have you changing things around because you suddenly have an idea.”

“And who the hell are you to tell me what I can, and can not do, in my own house?” Dad reacted.

“I’m the one who loves you, Daniel—in spite of yourself and everything you’ve done to push me away,” Mom said in a soft voice. “I’m the one who stands beside you— even when you think no one loves you anymore. But I won’t let you stand here and tell me that you’re going to lock yourself in this room and follow the war, when we both know it’s just an excuse for you to hide from everything. The only war you have to fight is locked inside of you, and the sooner you realize that, the better off you’ll be—the better off we’ll all be.” I saw him melt in front of her.

I looked at Winnie. She had registered with the Women’s Nursing Corps the week before, and it was only a matter of time before she got the call for active service. She assured me that she’d be stationed somewhere in England—most likely in London—and that she’d be safe.

I had a hard time believing her—there was little hope for anyone to hold onto with what was happening in the war at the moment—and seeing how determined Dad was to follow Jack through the war, I wondered what he’d say once he found out Winnie was leaving as well.

The evacuation at Dunkirk came as a shock to everyone. 340,000 troops belonging to the British Expeditionary Forces in full retreat; through a combination of both naval vessels and hundreds of civilian boats, most of them were saved. German airplanes flew overhead strafing the beaches and the Channel with machine gun fire as well as dropping bombs.

Dad took the news hard; Mom cried. It would be three weeks before news of Jack’s safe return reached us.

It was the first painting Dad made.

I had no idea that Dad was a painter before the Great War. He’d doodle and draw small animations for us: Mickey Mouse; Donald Duck; Bugs Bunny and Elmer Fudd—but that wasn’t painting, was it? Not like what he was doing now. His doodles almost all consisted of three-dimensional shapes: designs that had no thought, no rhyme nor reason, and no purpose other than killing time. He doodled on the backs of envelopes, or any scrap piece of paper he could find. They never looked exactly the way they were supposed to: Mickey’s nose didn’t line up properly, and Bugs’s teeth were never the right size.

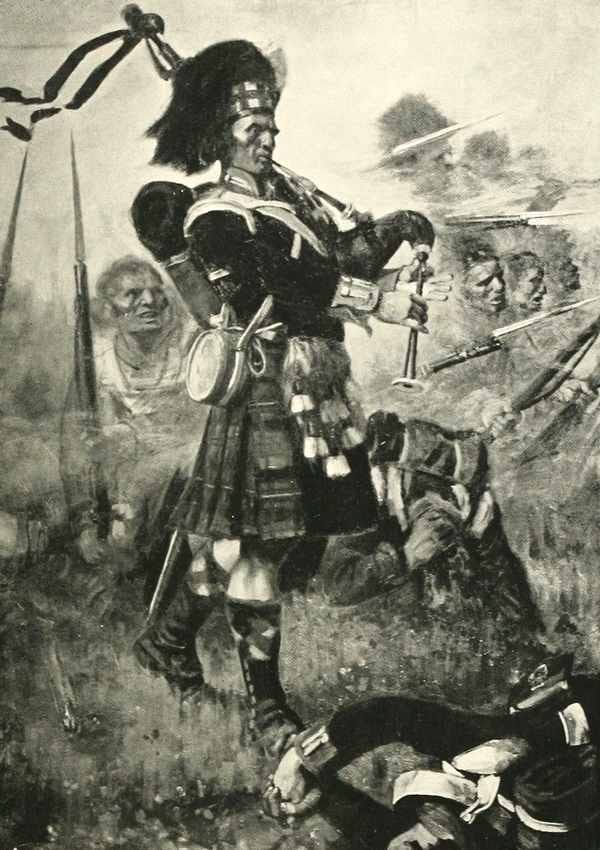

His vision for the withdrawal at Dunkirk involved a Scottish Piper in Full Highland Dress, standing knee-deep in the surf, with his back to the observer’s eye as he faced a German airplane strafing the beach. He was holding his bagpipe by one of the drones, and it was dragging in the water; his feather bonnet lay beside him in the sea foam like a wounded thing. The water was a red wash around him. He was looking out over an enormous seascape of landing crafts, ships, fishing boats, and pleasure crafts, all fighting the rough seas while thousands of soldiers—hundreds of thousands—lined the beaches fighting against the strafing fire of German planes, and exploding bombs. The Piper at the Gates of Hell, he called it. A large watercolour he painted with a light wash on the front of the map where he’d drawn the red circle around the name DUNKIRK—the very spot where the stain of blood surrounded the piper. You could see an outline of the map underneath all the turmoil of the failed invasion.

“How do you even know there was a Piper there?” I wondered out loud.

“My son,” he said, chewing around the stub of his cigar. “They’re British. Believe me when I say, if the British are involved, there’s a piper; it’s how they do things.”

I accepted his explanation as easily as I accepted his formally addressing me as “my son”. He said it with what amounted to a hint of reverence—as though he were telling me something I should be approaching with a sense of awe. He used to speak to Jack like that whenever he wanted to tell him something he felt it was important for him to know.

“How come you never painted before?” I asked.

“Before what?”

“Before this,” I said, and pointed at the painting.

He scratched at his the hole under his patch as he thought about it, and then smiled.

“I did. But it was a long time ago.”

“You mean before the Great War?”

He nodded.

“And you stopped because of what happened during the war?”

“I stopped because I lost my arm,” he said around a smile.

“You mean it wasn’t what you saw?”

“I used to be left handed.”

I was stunned. I’d had no idea.

“How do you know what the fighters look like? Or the landing crafts? How do you even know what the soldiers are wearing? They can’t be wearing the same things they did when you were there.”

He pulled out a section of newspaper from under his paints and handed it to me. There was a long parade formation of soldiers walking through the streets of Toronto, and I could see the same basic formation on the beach. There was another picture of a dive-bomber in the battle of Warsaw, and it too was in the painting.

“So who’s the man?” I asked.

“What man?”

“The Piper? Who is he? Someone you know, or knew? I mean, everything else you have in it is things you’ve taken from other pictures, why should he be any different?”

He was silent for a moment as he washed his brush in the murky jar of water to his right.

“He was a friend,” he said.

This is exquisite, Ben. I don't know how you have been able to capture so well the doubt, the determination and the sorrow that was such a part of this era. Such a rich story. Kudos, to you brother.

I really enjoyed hearing you read your story. Thank you