1 Paris 1956

Martin Jakob sits in the narrow dressing room listening to the sound of the crowd outside slicing through the night club with a raucous rumble of laughter. The music echoing through the club seems to linger like an old friend who’s overstayed his welcome. He pulls off the Marilyn wig he’s wearing and tosses it on the dressing table; pulling off the beauty mark which he sticks on the cracked mirror.

He tried not to look at his reflection because it made his eyes look disjointed, split and maladjusted, but he can see that the black spot he just placed on the mirror is perfectly set if he doesn’t move his head. For a moment he doesn’t, he just sits still, looking at his broken reflection. His can see his lips are still red, but not as vibrant as they were earlier; his cheeks look faded, the rouge is streaked with sweat, and he hesitates for just one more moment before he picks up the rag and begins scraping at the make-up.

He knows he isn’t the same handsome man he was in his youth. At fifty-three, he accepts this; he can see reappearing lines that betray his age as he cleans the pancake make-up off his face. The war years were hard — not just for him, but for everyone. I’m left with nothing but memories, he thinks, looking down at the numbers tattooed on the inside of his forearm. He knows that memories are something men like him try to forget, or not being able to forget, at least hide.

There’s no hiding from that past though, is there?

He picks up his battered package of cigarettes from the dressing table. He lights a cigarette and sits back, blowing the smoke up at the water-stained ceiling. Maybe, if there was more than just the span of his own lifetime separating his past from his present, he thinks; maybe, if somehow — miraculously — he was already at the end of his life — that he’d already run the race, done the course, and did the deed — then maybe the memories wouldn’t seem so final? So complete? Maybe, he might even be lucky enough to lose a few of those memories along the way? A rare thought, he thinks, but one he’s willing to hold on to.

He hears the crowd outside again — hears the music, hears the cheering, even the catcalls — and sits forward in his chair. He puts the cigarette down and once again picks up the rag and starts to clean his face, but he sees the tattoo again, and pauses. He stares at it. He remembers how once he thought he’d visit a tattoo parlour and have the numbers covered. The artist refused though, showing Martin his own numbers. The man offered to ink a Star of David under the tattoo, but Martin declined, telling the man not everyone who survived the Camps was a Jew. He left it at that. There was no need for him to explain himself.

Having the numbers on my flesh is explanation enough.

He picks up his cigarette, takes a deep drag, and blows the smoke up at the ceiling again. He knows that having survived will never be enough for some people — not having survived the way he did — while others feel overwhelmed by it all, and think it’s too much, which is what he feels whenever he thinks about what happened. He wonders if it’s guilt he feels for not having suffered enough in their eyes?

Is that what they call Survivors guilt?

And because of his past and everything that happened, he ended up here, instead of on the various other stages he enjoyed playing in his youth. He played on stages in Berlin, Hamburg, and Munich; in London, Amsterdam, and even Madrid. Now, instead of playing for a select audience of aristocratic snobs full of their pretentious opinions and their bloviated speechifying, he finds himself in a Paris nightclub playing for a roomful of foreigners — homos, lesbians, and sexual deviants — they’ve come to watch raucous sex shows while he plays Chopin on the piano, dressed like Marilyn Monroe.

I let this happen to myself.

Could he have ever imagined himself here, when he was still that young piano playing protégée in Germany? Unlikely. He catches his reflection in the mirror, and hesitates. It’s almost as if he can see his younger self. The crack in the mirror runs down the centre of his face, and he tells himself there’s nothing left of that life now — not even his memory of the Beethoven Kiss, he thinks. Now, it’s nothing more than a memory that’s been handed down through generations and just as quickly forgotten. He realizes that it’s the loss of his former life and everything it had to offer that hurts the most.

Or is it losing Dieter?

There are times when he thinks his life itself is a betrayal.

But then, how could anyone have imagined the world would implode on itself and become engulfed in yet another cataclysmic War? And not just a War for the sake of conquest, or supremacy — or even a War to end all Wars — but a War with complete and total annihilation in mind; a War built on the wholesale slaughter, and genocide of a people; a razing of cities that would divide an entire continent — the entire globe — and destroy an entire generation.

Did we learn anything from it?

He stabbed his cigarette out in the ashtray. If the world learned anything over the last ten years, it’s that War will never be eliminated; it can never be defeated. There will always be a political despot somewhere in the world wanting more; a dictator who is willing to take what he wants because he’s stronger, and willing to make the sacrifices others won’t. There will always be soldiers, somewhere, willing to follow orders — blindly — even knowing the “I-was-just-following-orders” defence, fails to stand up to scrutiny.

The world’s full of hate, he reminds himself, picking up another cigarette and lighting it. There will always be victims willing to let others put numbers on their arms because the alternative is dying, and no one wants to play the martyr. He knows this first hand. He’s witnessed it; he’s lived it. The only thing that saved him during the war was the fact that he once played for audiences across Europe; it doesn’t matter that he’s the last surviving inheritor of Beethoven’s Kiss, something that’s been passed down through successive generations.

A moment after he arrives, Bijou enters the dressing room, followed immediately by La Niña. Both of them are laughing, covered in sweat. They’ve come to change their costumes — or as much costume as their sweaty sex show allows them — and Martin watches as they prepare for the second show of the night. It’s all sequins, and feathers this time, with grand feather boas. It promises to be a long night, Martin thinks, as he prepares for the next set and begins applying fresh make-up. He picks the wig up and puts it on, reaching for the beauty mark, and notices Bijou watching him.

“What are you looking at, you saucy little minx?” he says.

“I was just trying to imagine myself as a washed-up, aging queen,” Bijou laughs. “I couldn’t.”

“Oh, darling, you’re so mean,” La Niña says with a laugh. “I’m not saying you’re wrong, just mean.”

I'm so glad you're starting anew serial. I'm already fully in the story and the character. Brilliant, Ben!

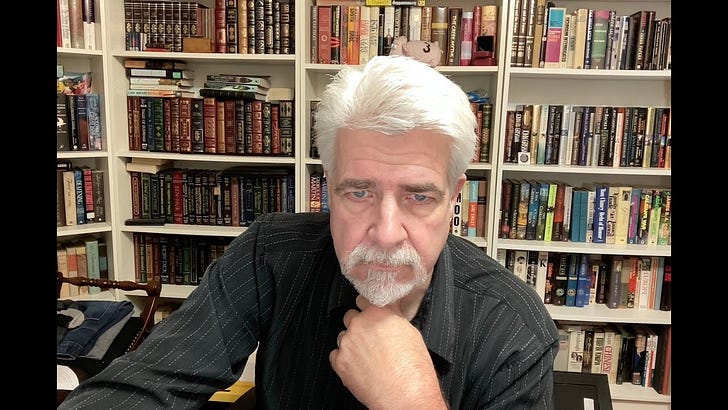

Just fantastic Ben. Great piece of writing. You've got a gift. - Jim